The Trial and Execution of Charles I

The trial and execution of Charles took place in January 1649, with his death marking the end of Stuart rule in England until the restoration of the monarchy 11 years later. After Charles’ execution, Oliver Cromwell, whose signature can be seen on Charles I's death warrant, gradually established himself the ruler of England.

The trial of Charles I was unprecedeted as there were, at the time, no precedents or rules in place that could be used within the trial of royalty. As a result, Dutch lawyer Isaac Dorislaus was forced to write an order that could be used in court as a framework to structure the trial. This framework was based on the law of the Roman Empire that was used to empower military to overthrow any leader deemed by them to be tyrannical.

Once the order was created, the trial of Charles I could begin. The trial started on 20 January 1649 in London, where he was accused of being a "tyrant, traitor and murderer; and a public and implacable enemy to the Commonwealth of England".

Initially, there were supposed to be 135 judges in attendance at the trial, but only 68 were recorded as having attended. This is likely due to the fact that many had no rish to be involved in the trial of a member of the royal family. Similarly, there were many MPs who were unhappy supporting such a trial, although they had all been removed from Parliament by the army in December 1648 as part of 'Pride's Purge'. Those MPs left formed what was known as the 'Rump' Parliament, which was 46 men who were counted by Oliver Cromwell as supporters. Even so, only 26 of these MPs had voted to try the king, signalling how revolutionary this decision had been.

The Chief Judge of Charles' trial, John Bradshaw, acted as head of the High Court of Justice. Aware that the trial was incredibly unpopular, he was reportedly concerned that he may be targeted by murderers for his role. As such, he made himself a hat that was lined with metal to provide him with protection if he were attached.

At the beginning of the trial, Bradshaw read out the following charge against the king, and so marked the start of one of the most famous trials in history:

"Out of a wicked design to erect and uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people of England."

The trial was held in a hall that was lined with soldiers, although it was never established whether this was to keep MPs safe or to prevent the escape of Charles I, who had already escaped capture before. Either way, the King made no attempt to defend his actions due to his belief in the divine right of kings - he believed that no king should be put on trial by members of the public and had no respect for the process that took place before him. This was reflected in his refusal to remove his hat in court, which was a display of disrespect for the judges.

Without any defence, Charles' trial was short and it did not take long for him to be found guilty and have his punishment declared. On 27 January 1649 Bradshaw announced the judgment of the court:

“He, the said Charles Stuart, as a tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy to the good of this nation, shall be put to death by severing of his head from his body."

Once this verdict was delivered, however, Charles began to plead his case. But this was in vain, and he was told it was too late. The judge set his date of execution as 30 January 1649.

The day of the execution was a Tuesday, with reports stating that it was cold, grey day. The King was given permission to go for a walk with his dog in St James’s park before he was given his last meal, which was bread and wine.

However, execution proceedings were delayed as several executioners had refused to execute the former king despite being offered masks to hide their identities. Eventually, a man and his assistant were paid £100 to carry out the act.

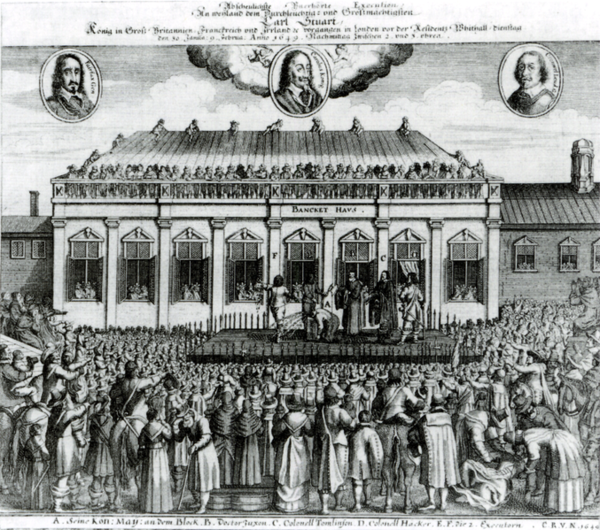

At around two o’clock, Charles was led to the scaffold. He was worried that any shivering would be perceived as fear and so requested that he could wear thick underclothes to protect him from the cold. On the scaffold Charles gave a last speech to the crowd:

"I have delivered to my conscience; I pray God you do take those courses that are best for the good of the kingdom and your own salvation."

It was reported at the time that a large groan travelled through the crowd when he was beheaded, with one observer described the noise as "such a groan by the thousands then present, as I never heard before and I desire I may never hear again".

Charles’ dead body was subjected to a number of humiliating rituals as part of his punishment. After paying, those in attendance were allowed to dip handkerchiefs in his blood as many people believed that royal blood could be used to heal wounds of cure illness.

On the 6 February 1649, parliament abolished monarchy, stating:

"The office of the king in this nation is unnecessary, burdensome and dangerous to the liberty, society and public interest of the people."

The Council of State replaced the monarchy, with Oliver Cromwell named as its first chairman.

During the Restoration of 1660, when Charles II came to throne, the new king hunted down all those who had signed his father’s death warrant and executed them as regicides. The executioners managed to evade the wrath of the new monarch, however, as no one ever discovered who the two men were.

See also:

The Execution of Charles I

MLA Citation/Reference

"The Trial and Execution of Charles I". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.