Mutiny in the French Army

In the spring of 1917, the French Army faced what was arguably their greatest test of World War One - widespread mutiny.

The mutiny was largely kept quiet, with Ludendorff stating in a letter written after the war that he had known nothing about what was going on. However, within the upper reaches of the French Army many officers had expressed serious concerns about how the mutiny could affect their plans, particularly as some of the soldiers were flying red flags and singing the ‘Internationale’, potentially in sight of the Germans.

The mutiny began following the Nivelle Offensive, which took place in April 1917 and was a severe failure, costing the lives of many thousands of French soldiers. By the middle of the month, it became very clear that many of the infantrymen had simply had enough, and the mutinies began on 17th April - one day after the offensive had failed.

The beginning of the mutiny was marked by 17 men from the 108th Infantry Regiment leaving their posts ‘in the face of the enemy’. Twelve were sentenced to death but all were reprieved, which G Pedroncini (‘The Mutinies of 1917’) suggests was the correct decision. According to Pedroncini, the decision of the soldiers was largely motivated by the conditions of trench warfare, as well as the large periods of time between leave. Additionally, he stated that the singing and waving of red flags were simply gestures of their displeasure rather than full mutinies.

In general, the French soldiers had positive relationships with their junior officers, who regularly fought with them at the front. However, it was the senior officers who were responsible for the strategy and tactics who were regarded less highly. However, there was only one recorded cause of an assault - on General Bulot - and the senior commanders often managed to reduce tension by meeting with the mutineers to discuss their issues. This was often enough to bring the soldiers back to the front line.

It’s often argued that one of the main causes of the mutinies was the spread of rumours, with two in particular causing great issues for the officers. One such devastating rumour was that every tenth man in the battalions of the 32nd and 66th regiment were to be shot as punishment for refusing to obey orders. Three mutineers were sentenced to death, but only one was killed. However, the rumour still caused a great deal of anger.

The second rumour was that the woman and children of Paris were being attacked and abused by rioters in the city while the French men were engaging in pointless battles on the front line. While there had been disturbances in the city, the rumours were actually greatly exaggerated.

While refusing to obey orders, the French mutinies were largely peaceful. When the soldiers of the 74th Regiment were ordered to move forward on 5th June 1917, 300 passed a resolution that they would not go back to the trenches. However, they simply marched to the nearest village and sat in the road in protest. Similarly, when the men of the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 18th Infantry Regiment were ordered to go back to the front line, having been previously promised generous leave, they refused to obey orders but told the colonel that they had nothing against him personally, shouting ‘long live the Colonel’.

The mutinies within the French Army took place between 17th April and 30th June, with a total of around 250 instances across the army. Most commonly, the mutineers argued that they were not given enough leave, with very few actually refusing to face the enemy.

In total, it’s thought that around 35,000 men were involved in the mutinies, from an army of around 3,500,000 men. While this was a relatively small number (just one per cent), the French commanders were still concerned. One of the main reasons for their concern was that many of the troops involved were part of the reserves, which meant that they may be unavailable to move to the front when Germans launched an aggressive attack on those already there.

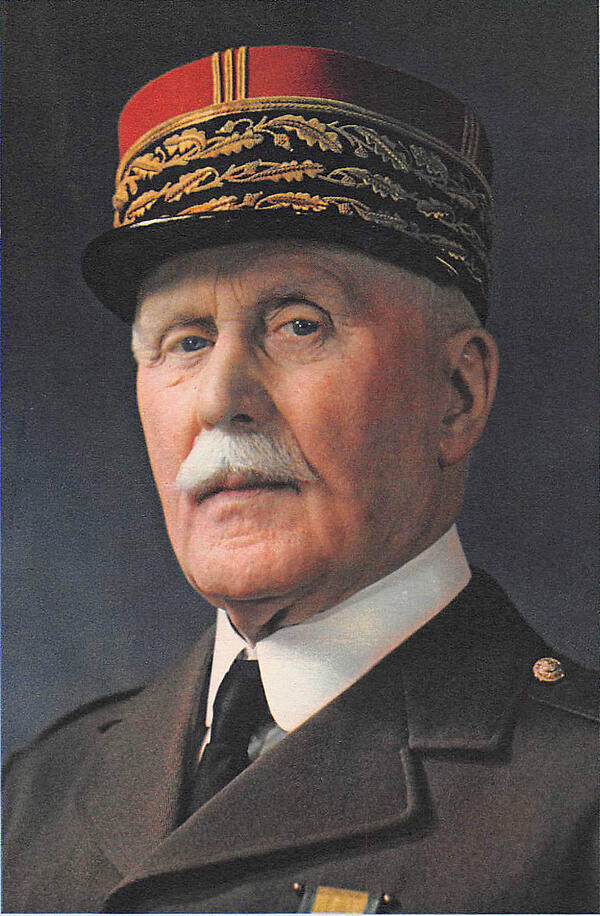

Despite these worries, the mutinies had almost all ended by the end of June, with the Germans never having realised they were taking place. General Philippe Pétain, new commander of the French armies in the northeast and replacement for Nivelle, was given the task of solving any issues that the mutineers still had and dealing with those who were causing trouble.

While Pétain took his tole seriously, he only wanted to instil discipline rather than instigate a policy of complete repression as other officers had done before him. He wrote on 18th June 1917:

“We must prevent the prolongation of disorders by modifying the environment in which these malevolent germs found a favourable terrain. I shall maintain this repression with firmness, but without forgetting that it is being applied to soldiers who for three years now have been with us in the trenches and who are “our” soldiers.”

The army immediately plunged the whole affair into secrecy, making it hard for historians to gain any real punishment numbers even once the war was over. Nevertheless, G Pedroncini managed to pull together the following statistics:

- The French Army consisted of 112 Divisions and 68 were affected by mutiny.

- Of these 68, 5 were “profoundly affected”’ 6 were “very seriously affected”, 15 were “seriously affected”, 25 were affected by “repeated incidents” and 17 were affected by “one incident only”.

- A total 35,000 men were involved in mutiny.

- 1,381 were given a “heavy prison sentence” of five years or more hard labour. Twenty-three men were given life sentences.

- 1,492 were given lesser prison sentences, though some of these were suspended.

- 57 men were probably executed (7 immediately after sentence and possibly another 50 after they received no reprieve. There were 43 certain executions (including the seven summarily executed) and 14 “possibly” or “doubtfully”. Two more men were sentenced to death but one committed suicide and one escaped (Corporal Moulin who was known to be still alive after World War Two).

- It is known that of these 57, some were not executed for mutiny but for other crimes committed in the time when the mutinies occurred, including two men shot for murder and rape.

Therefore, fewer than 3,000 men received some form of punishment out of a total of 35,000.

Pétain remained true to his word, ordering that the French Army should take no further part in offensives until the time was right, and stating that leave should be granted at the end of every four months as was initially promised. He also worked hard to improve the quality of the food and bedding to ensure the soldiers had a more comfortable day-to-day life. This approach worked, and a secret report written in July 1917 for the Grand Quartier Général by the Special Service Bureau stated:

“The sense of discipline is returning. The average opinion among the troops is that at the point we have reached it would be absurd to give up. But the officers must not treat their men with haughtiness.”

MLA Citation/Reference

"Mutiny in the French Army". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.