British submarines and the North Sea

British submarines played a vital role in the North Sea during World War One, remaining there for the duration of the war and having an enormous impact on the outcome of the British naval campaign. The most important role the submarines played was the assist with the blockade of Germany’s coastline.

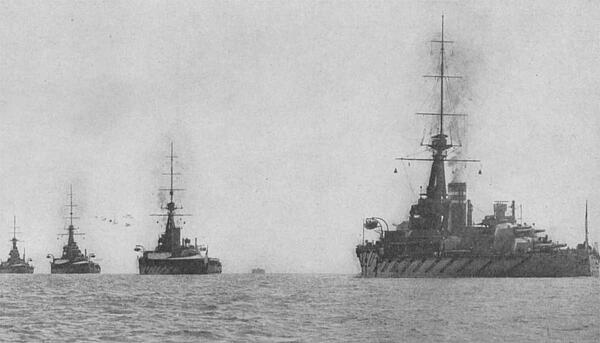

There were two types of blockade: naval and commercial. While these blockades regularly overlapped, the naval blockade was primarily concerned with preventing enemy ships from leaving port, while commercial blockades would focus on preventing supplies from entering key locations. Distant blockades were also introduced as a way of preventing enemy ships from leaving key areas, even if they could not be trapped in ports or harbours. This tactic was used by the Royal Navy in July 1914, when the Admiralty ordered a distant blockade to trap the German High Seas Fleet in the North Sea and prevent it from entering the English Channel.

When Britain declared war in august 1914, it took just four hours for three E-class submarines to begin patrolling the North Sea. This forced merchant ships to pass by the main Royal Navy fleet, who confiscated cargo destined for Germany, or to risk facing the submarines.

In total, nine submarine flotillas were established in 1914, with four of these patrolling while the others were focused on coastal defence. The high number of submarines sent to defend Britain’s coast was a reflection of the general fear among the Admiralty that Germany would attempt to invade Britain. However, First Sea Lord Jackie Fisher believed the Royal Navy was capable of defending the coast on its own, and that submarines were better used elsewhere.

In fact, the E-class boats that were allowed to patrol the North Sea were hugely effective, particularly as there was no way of enemy ships detecting them when the war began. However, the Admiralty continued to see them as a form of defence rather than as a weapon, and in 1916 they were even used to report information on ships rather than attack the enemy. British submarines were also banned from attacking the German fleet in some cases as the Admiralty wanted them to leave the harbour.

During World War One there were three naval battles that took place in the North Sea, although only the Battle of Jutland was considered to be major and no submarines took part in this. One of the main reasons was the lack of communication with submarines; while surface ships could receive new information from each other and act accordingly, submarines were unable to receive from new details and could only work from their initial brief.

This problem was the downfall of Britain in the Battle of Heligoland Bight. Fought on 28 October 1914, the battle began with three submarines (D-class and E-class subs) enticed German destroyers and cruisers out of Wilhelmshaven while another three submarines waited to attack further ahead. A separate Admiralty order had set out the Harwich fleet commanded by Commodore Tyrwhitt to engage the Germans. During the battle, British surface ships (who had no idea the submarines were in the area) began to fire on British submarines, who then tried to return fire. P G Halpern wrote of the battle:

"I was very much concerned, as the submarines had no idea of their presence and I greatly feared that they, particularly the light cruisers, might be attacked by the submarines..........E-6 on two occasions got within very close range of one of our light cruisers and only refrained from firing when he actually distinguished the red St. George Cross."

Sadly few lessons were learnt from the battle, and at the Battle of Dogger Bank they ran into the same problem. British submarines had the chance to sink German cruisers but they had been told to expect British ships in the area, so they let them pass by. This was all due to a lack of communication, and the damage done to the German fleet could have been great. Unfortunately, G Keyes, captain of the Submarine Service, was blamed for the failure and relieved of his post in February 1915.

Jutland saw similar issues, with British submarines being told that they were to rise from the sea on 2 June 1916 and engage with the German High Seas Fleet. However, the retreating German fleet passed over on 1 June, once again reflecting the communication problems that were rife within the Royal Navy during the first few years of submarine use.

The Submarine Service was once again blamed for its ‘failures’ and the Admiralty found other tasks for it in the North Sea. Ironically, their most successful role was in anti-submarine warfare. On more than one occasion, submarines were towed near to U-boats that were threatening British fishing fleets, and the U-boat was destroyed. This tactic worked well until German POWs informed the German High Command and it was found out. Despite this, it bought the fishing fleets some peace, according to W G Carr’s “Hell’s Angels of the Deep”:

"These two actions had a great moral effect on the crews of the enemy submarines. Our fishing boats were not interfered with again until well into 1916. There is little doubt that the mysterious loss of two boats sent out within a month of each other on what might be considered a safe mission, caused the enemy to abandon the campaign against the fishing boats."

British submarines were also involved in Admiral Beatty’s plan “Operation BB”, which involved placing destroyers on the northern coast of Scotland to encourage German U-boats to dive. They would then resurface when out of danger but face attack from hidden K-class submarines. Despite no submarines destroying any U-boats, three more submarine bases were established around Ireland and in the later stages of the war the British subs managed to sink 18 U-boats.

The K-class submarine had been developed to allow submarines to keep up with the speed of surface vessels. However, the steam-powered vessel was hailed a disaster. This was partly due to the fact that it was designed to be used above the water in many instances, including to use the radio, but it took over five minutes for it to dive down compared to the 30 seconds of the submarines that went before. This made it vulnerable to attack and ultimately not seaworthy.

In spite of this, the Admiralty ordered another 13 K-class submarines to be built, but they were all prone to serious leaks and took between 15 and 20 minutes to get into position to attack a U-boat - removing the element of surprise. The Admiralty refused to see the faults in the vessel, claiming that issues were caused by human error. However, those who sailed in them had very different views:

"I never met anybody who had the least affection for the K-class and they were looked on with fear and loathing. After all, they murdered many of their officers and crews." (D Everitt)

"The only good thing about a K boat was that they never engaged the enemy." (Rear Admiral Leir)

MLA Citation/Reference

"British submarines and the North Sea". HistoryLearning.com. 2024. Web.