The Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps was first created in May 1912. However, just two years later it became a crucial part of the war, used as the eyes of the British Army to direct artillery gunfire, take photographs for intelligence and taking part in airborne battles with the German Air Service.

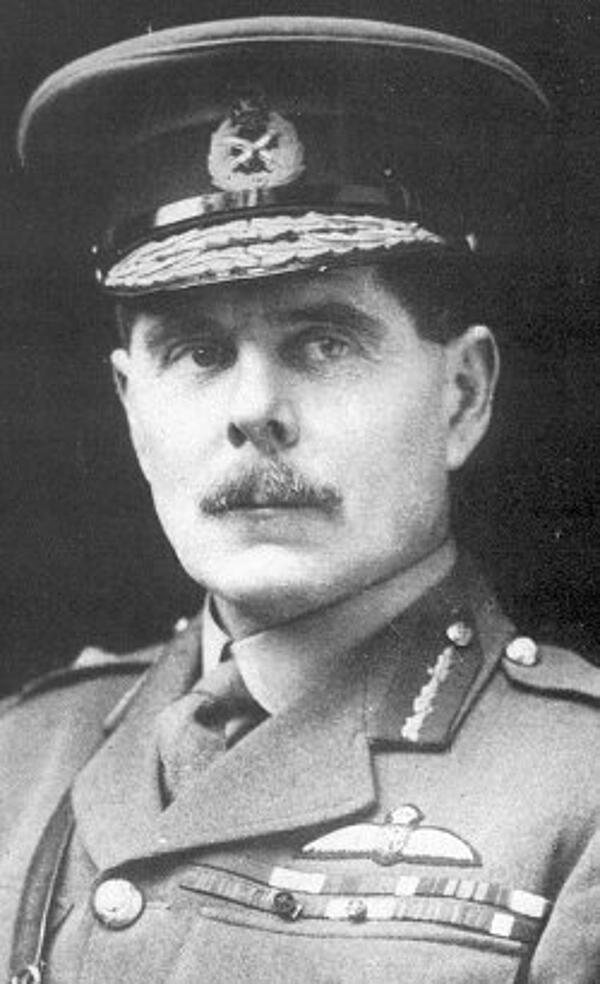

Part of the British Army, the Royal Flying Corps’ first commander was Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson who watched over two separate sections - the Military Wing and the Naval Wing. By 1914, however, the Navy Wing had been put under the direct control of the Royal Navy and this marked the formation of the Royal Naval Air Service.

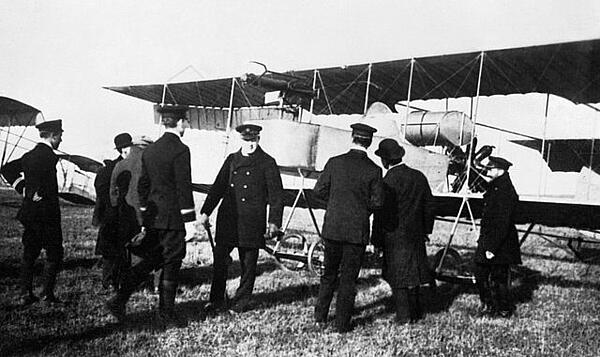

With flying still in its infancy during this time, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) aeroplanes were relatively crude, with many of their planes not really capable of engaging in classic aerial combat. This meant that the initial work of the division was intelligence based and didn’t involve a lot of direct engagement with the enemy.

This all changed when Hugh Trenchard was put in charge of the RFC, when pilots were suddenly expected to be more aggressive in their approach.

The RFC were first put into action on 19th August 1914, six days after leaving the UK for its French base. The planes were so crude that they were forced to fly along rivers and coastlines, with many being turned around due to poor weather conditions.

Despite this slow start, the RFC still played an important role in many of the early battles, including the First Battle of the Marne. The pilots were able to act as the eyes of the British Army, providing commanders on the ground with vital information. In fact, the RFC were responsible for telling commanders that the German First Army was preparing to attack an exposed French position, which gave the French time to re-deploy its men and counter the assault.

This effort earned them great praise:

“I wish particularly to bring to your Lordships’ notice the admirable work done by the RFC under Sir David Henderson. Their skill, energy, and perseverance have been beyond all praise.”Sir John French

Despite their success, the British Army still felt it necessary to modernise their aerial service and extensive development took place throughout the war. In fact, the service started to develop aeroplanes that had specific roles, with Hugh Trenchard acting as the driving force behind this.

This period of development intensified after 31st May 1915, when a German Zeppelin attacked London having travelled 400 miles without being brought down by any Allied forces. This led to a bombing raid that killed five civilians and injured 35. While these numbers were minimal compared to the casualties in Europe, the impact on London and Britain as a whole was enormous as it brought the war home.

This reality check only continued when, on 13th June 1915, 14 Gotha bombers attacked the Capital. A bomb hit a school, killing 18 children. The desire for revenge was overwhelming and Trenchard felt that the enemy’s government could be weakened significantly if civilians became targets and the government was forced to deal with mass panic.

The RFC was supposed to play a crucial role in the Battle of the Somme, providing crucial intelligence to ensure the infantry didn’t advance at the wrong time. However, low cloud meant that the flights could not take place and the troops moved forward blind. The RFC did still play a part, however, and 800 aeroplanes weer lost between July and November 1916, killing 252 crew.

The RFC also suffering difficulties in light of the German developments, which seemed to be progressing faster than the British. The German ‘Albatross’, for example, was a much stronger plane than anything produced by the RFC during the war. This led to many British planes and pilots being taken. In April 1917 alone, the “Fokker Scourge” led to the RFC losing 245 aircraft, with 245 being killed and 108 taken prisoner. Meanwhile, the RFC only shot down 66 German planes.

These losses spurred the RFC on and by the summer of 1917 it was equipped with aircraft that were finally the equivalent of the German offerings. Both the Sopwith Camel and the Bristol Fighter, for example, were considered to be excellent planes.

In August 1917, the government received a report from General Jan Smuts that a new air service should be introduced that would be the equal to the British Army and Royal Navy but separate from them both. This view was taken on board and the Royal Air Force was introduced on 1st April 1918, with Hugh Trenchard named as its first commander.

During the First World War, the RFC, Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force lost a total of 9,378 men with 7,245 wounded. They managed to log around 900,000 flying hours in this time, with just under 7,000 tonnes of bombs dropped on enemy positions. As a result of their actions, eleven members of the RFC were awarded Victoria Crosses and some pilots even became household names, including Albert Ball and James McCudden.

MLA Citation/Reference

"The Royal Flying Corps". HistoryLearning.com. 2025. Web.