With the centenary anniversary of several bloody battlegrounds including the Somme and Verdun, this blog assesses why, after 100 years, historians are still debating what started World War One.

The central question surrounding the start of the war is the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Historians have been at loggerheads as to how Europe went from the killing of a leader and his wife to the start of the largest conflict to date.

The need to not be shown as the aggressor

For the individual countries, the escalation to war must not be seen by the population as an act of aggression. In the months of July and August 1914 the governments of France, Russia, Great Britain, Germany and Austria-Hungary, had to appear as if they were only defending their nation’s affairs. A massive deployment of troops could not be utilised if one of the countries did act aggressively, as the socialist political climate would not have supported an aggressive foreign policy.

Both sides thought they were fighting a just cause. The British, Serbs, Russians, French and Belgians felt they were defending their nations for reasonable reasons and protecting each country’s sovereignty. The Germans, Austrians and Hungarians believed they were protecting their countries’ interests due to the aggressive nature of the assassination. Subsequently, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II declared that neighbouring countries had ‘forced the sword’ into its hands.

The victor writes the history books

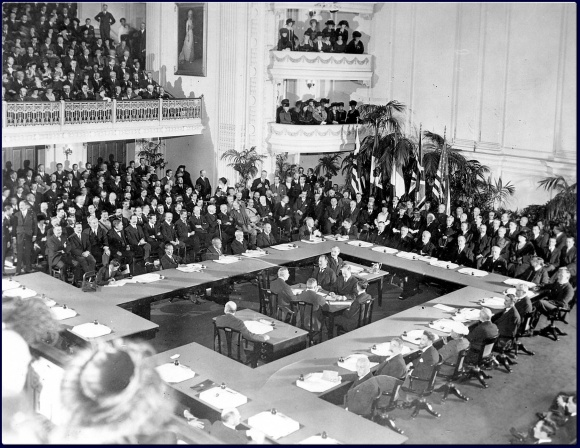

For the victorious countries, the aggressor was evident, and in 1919, at the Treaty of Versailles in Article 231 it was determined that Germany and her allies were ultimately responsible for causing World War One. As a consequence, Germany was ordered to pay severe reparations to the victors.

The Treaty, later to be dubbed ‘war guilt payments’ was to set in motion the current debate and from 1919 governments and historians have continually discussed who started World War One, from revisionists who argue that Germany was less responsible and wanted a revision of the Treaty of Versailles to the anti-revisionists who agreed with the victors assessment of the Treaty.

The revisionists have set about arguing that Germany was not to blame and have pointed to both Russia’s and France’s participation in the outbreak of war, but also to Britain, who could have eased the tensions before the crisis in July. During the period between the First World War and the Second, more views were formed as to the dynamics of the diplomatic system in place in Europe before 1914 and identified the gradual slipping ‘over the brink into the boiling cauldron of war’, as quoted by David Lloyd George.

In essence, this view was taken because of the need for a more conciliatory approach in the aftermath of one great war and also the rising concern of the recently formed Soviet Union. This was the accepted viewpoint up until the 1960s, when anti-revisionists, including the historian, Fritz Fischer, provided an alternative perspective to the status quo.

The anti-revisionists strike back

The first real historian to challenge the revisionist approach was Fritz Fischer. Fischer argued in a new thesis that Germany’s militaristic leaders had deliberately thrown the country headlong into the start of the war in pursuit of an aggressive foreign policy and desire to expand Germany’s borders. Supported by previously unknown evidence, this new work had a crucial effect on opening up the debate on who was ultimately responsible for the start of the Great War and primarily made Germany the main actor responsible for starting it.

Naturally, the revisionist historians were outraged at this new school of thought and attempted to discredit his thesis and its increasing amount of followers. Combined with the time where this divide happened, at the peak of the Cold War, this meant that the debate over who started the war was of considerable political significance in contemporary Germany.

No end in sight for debate

Gradually, the Fischer anti-revisionists approach was accepted but historians also began focusing on when Germany instigated war. Fischer was quite radical in his view that Germany wanted war as early as 1912. However, many historians have now conceded that Germany took full opportunity of the July Crisis to go to war.

Historians have also begun focusing attention on the role of Germany’s ally, Austria-Hungary, in the war, particularly the role it played immediately after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the events leading up to the Great War.

In recent years, historians have focused on both sides of the debate and a more generalist approach has been adopted looking at particular decision-makers. Germany’s and Austria-Hungary’s roles were lessened and looking instead at the governments and assessing to what extent they averted the war. After 100 years of debate, the argument over who started the war and who were the aggressors looks set to continue.