The Roman Civil War

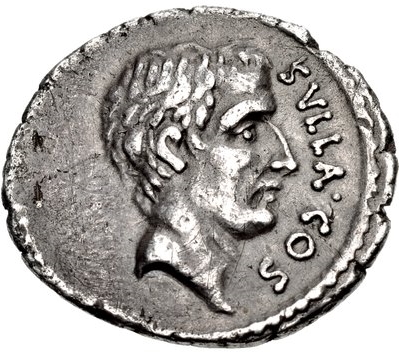

The Roman Civil War between Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla (88–82 BCE) marks a cataclysmic rupture in the Roman Republic, transforming its political landscape from a system of constitutional balance to one defined by militarized power struggles.

Chronicled by Plutarch, Appian, and Sallust, this conflict pitted Marius, the populist war hero, against Sulla, the patrician champion of the Senate, in a contest that escalated from political rivalry to outright warfare.

Rooted in the tensions of the Social War and foreshadowing Julius Caesar’s rise, the civil war exposed the Republic’s vulnerabilities, with its battles and political maneuvers reshaping Rome into a state where military might supplant civic authority.

Pre-88 BC: Origins in the Social War

The seeds of the civil war were sown in the Social War (91–88 BC), a revolt of Rome’s Italian socii demanding citizenship . Marius, a seasoned general from the Jugurthine War, and Sulla, his former subordinate turned rival, both distinguished themselves in suppressing the uprising. Their rivalry, however, festered over command and prestige, exacerbated by class tensions—Marius the novus homo versus Sulla the patrician. Sallust notes the divide: “Marius’s newness won the plebs, while Sulla’s lineage rallied the nobles” (Jugurthine War, 63).

88 BC: The Mithridatic Command Dispute

The spark ignited in 88 BC with the rise of Mithridates VI of Pontus, whose massacre of 80,000 Romans in Asia Minor demanded a response. The Senate appointed Sulla, then consul, to lead the campaign, affirming aristocratic prerogative. Marius, aged but ambitious, allied with tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus to seize the command through the comitia tributa, promising Sulpicius citizenship reforms for the newly enfranchised Italians. Appian describes the maneuver: “Sulpicius’s bill stripped Sulla of his army, handing it to Marius” (Civil Wars, 1.55). Sulla’s reaction was unprecedented: he rallied his six legions—loyal from the Social War —and marched on Rome, the first Roman general to do so. Plutarch recounts: “He stormed the city, scattering Marius’s faction” (Life of Sulla, 9). Marius fled to Africa, leaving Sulla to restore senatorial control before departing for the East.

87 BC: The Marian-Cinnan Coup

Sulla’s absence emboldened Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna, the latter elected consul in 87 BC. Denied entry to Rome by the Senate, Cinna raised an army of Italian veterans and exiles, joining Marius upon his return from Africa. Their strategy was siege-based: they blockaded Rome, severing grain supplies from Ostia and Campania. Appian details the desperation: “The people ate dogs and leather… corpses piled in the streets” (Civil Wars, 1.68). The Senate capitulated, and Marius entered with a vengeance, unleashing proscriptions that slaughtered Sulla’s allies—senators, equites, and citizens alike. Plutarch records the terror: “Lists of the damned were posted daily; none dared bury the dead” (Life of Marius, 43). Marius secured a seventh consulship in 86 BC but died days later, leaving Cinna to consolidate power.

86–83 BC: Sulla’s Eastern Triumphs and Preparations

In Greece, Sulla prosecuted the First Mithridatic War, decisively defeating Mithridates at Chaeronea and Orchomenos (86 BC). His strategy relied on rapid assaults: at Chaeronea, he used entrenched positions to repel Pontic phalanxes, while at Orchomenos, he channeled enemy cavalry into marshlands for slaughter. Polybius (via Appian) praises his ingenuity: “He turned terrain into a weapon, crushing their numbers” (Civil Wars, 1.50). The Treaty of Dardanos (85 BC) imposed fines on Mithridates, freeing Sulla to plot his return. Declared a public enemy by the Marian regime, he amassed wealth and a loyal army of 40,000, poised to reclaim Rome.

83–82 BC: The March on Italy

Landing at Brundisium in 83 BC, Sulla advanced northward, exploiting Marian disarray. His political acumen shone: he won defectors like Gnaeus Pompeius (later Magnus) with promises of land and honors, swelling his ranks. The campaign’s decisive moment came at the Battle of Sacriportus (82 BC) against Gaius Marius the Younger, Cinna’s successor. Sulla, outnumbered, feigned retreat across a river, luring the Marians into a disorganized pursuit. His cavalry then struck their flanks, while legions reformed to crush the center. Appian narrates: “The enemy broke in confusion… thousands drowned in flight” (Civil Wars, 1.87). This victory opened the path to Rome.

82 BC: The Battle of the Colline Gate

The war’s climax unfolded at the Colline Gate, Rome’s northeastern threshold, on November 1, 82 BC. Sulla faced a coalition of Marian remnants and Samnites under Pontius Telesinus—50,000 strong. Positioning his legions on high ground, he absorbed an initial assault, then unleashed a counterattack with cavalry led by Marcus Licinius Crassus on the right flank. The Samnites buckled, and a night-long slaughter ensued. Appian recounts the carnage: “Ten thousand fell… the city’s walls echoed with death” (Civil Wars, 1.93). Sulla’s triumph was absolute, though costly, securing Rome through sheer force.

82–81 BC: Dictatorial Reforms

Appointed dictator legibus faciendis et reipublicae constituendae in late 82 BC, Sulla wielded unlimited power to restore senatorial dominance. His proscriptions executed 4,700 foes, redistributing their wealth to loyalists, while laws curtailed tribunes, expanded the Senate to 600, and restructured provincial governance. Plutarch notes the irony: “He sought to heal Rome by cutting deeper wounds” (Life of Sulla, 30). Resigning in 79 BC, he died in 78 BC, leaving a fragile order.

MLA Citation/Reference

"The Roman Civil War". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.