The Warsaw Ghetto

The Nazis established ghettos for Jews and gypsies across Europe - the largest of which was the Warsaw Ghetto. Hans Frank, who was the top ranking Nazi based in Poland following Germany’s invasion in 1939, was the man entrusted with the task of setting up the Warsaw Ghetto. At its peak, as many as 400,000 Jews were based at the ghetto.

It was in the October of 1940 that Hans Frank declared that all Jews living in Warsaw were to instead be located in one particular closed of area of the city, that measured just 1.3 square miles - less than three per cent of the entire city. Overpopulation led to disease and starvation. Exactly one month after Frank’s announcement, on 16 November 1940, the ghetto was completely shut off from the outside world.

As was standard practice in the ghettos that the Nazis established across Poland, a Jewish Council was set up that would oversee the running of the area and collaborate with the Germans - in the Warsaw Ghetto Adam Czerniaków was the head of the council. While some accepted that cooperation with the Nazis was necessary, there were many Jews who did not want to help the invading Germans in any way. In Warsaw, like in Lodz, however, they knew they had little choice but to cooperate with the Nazis.

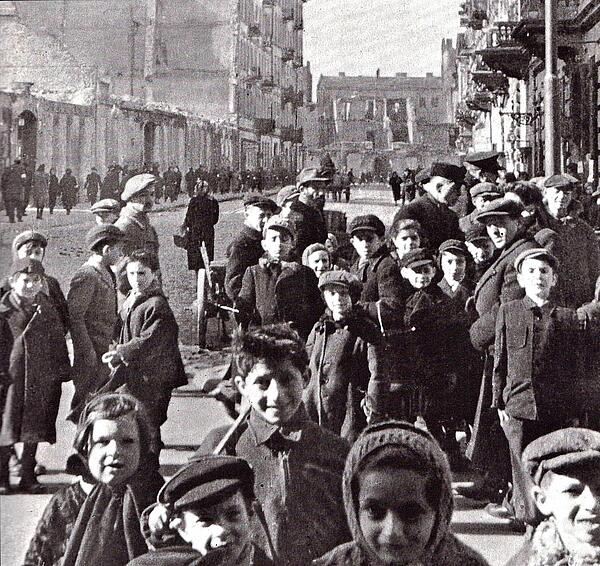

There was a steady flow of Jews and and other ‘untermenschen’ - the term given to people thought to be subhuman by the Nazi - entering the Warsaw Ghetto. However, the population reportedly stayed relatively constant at around 400,000. But conditions in the ghetto were appalling and that, along with the fact that medicine did not make its way into this enclosed part of city, meant the people’s health would suffer and disease was rife.

The Nazis overseeing the Warsaw Ghetto decided that each Jew only required 186 calories worth of food per day. As a result, even those who managed to avoid the diseases would rapidly become weakened, with around 100,000 Jews dying from hunger.

To combat the intense hunger they suffered from, Jews would resort to smuggling food into the ghettos. To do this they used young children who were harder to detect out of the ghetto zone of the city, get them to buy or steal food, then sneak back in, often using small tunnels dug under the fences. The children were small enough to get through the barbed wire or the small tunnels that had been dug. The penalty should they be caught doing so would be that Nazi guards would shoot them on the spot.

‘Operation Reinhard’, the name given to the Nazi’s plan to eradicate Europe of Jews by sending them to deaths camps, began in 1942. As a result, the Jews being held in the Warsaw were to be sent to the closest death camp: Treblinka. Somewhere between 250,000 and 300,000 Jews were sent from the ghetto in Warsaw to their deaths at the death camp at Treblinka between the months of July and September 1942 alone.

Although the Jews in the ghetto had originally be told that they were being taken away from Warsaw to be accommodate somewhere else, it soon became apparent that this was not the case and in 1943, when word spread about the fact they were being sent to their deaths, a revolt occurred. On 18 January that year, a group of Jews launched an attack of Nazi officers - such was the success of the attack that they managed to prevent the deportation of Jews and force the soldiers to withdraw from the ghetto, albeit only temporarily.

A rebellion like this could not be tolerated, however, and the Nazis returned to the city with increased forces in April and regained control of the Warsaw ghetto by the middle of May, killing many Jews in the process. Once they had suppressed the uprising the Nazis sent all the remaining Jews to be killed at the death camps, with the ghetto ceasing to exist by the end of May 1943.

See also: The Lodz Ghetto

MLA Citation/Reference

"The Warsaw Ghetto". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.