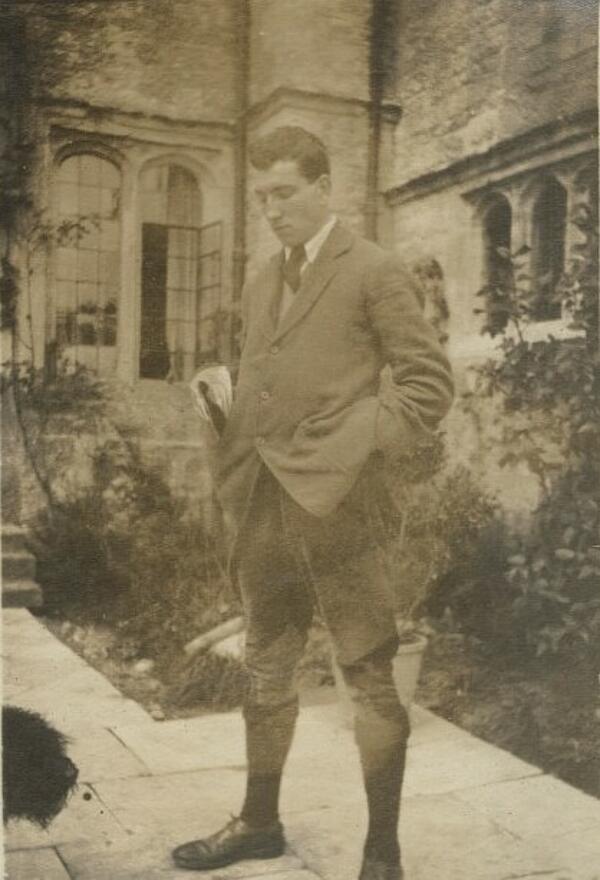

Robert Graves

Robert Graves is regarded as one of the foremost poets of World War One, and is considered to have been one of the few poets - alongside Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen and Rupert Brookes - who was able to put on paper the horrors of trench warfare.

Robert Graves was born on 28th July 1895 and educated at Charterhouse. During his time at school, Graves was heavily influenced by a teacher called George Mallory - who died in 1924 in his ascent of Mount Everest - and it was Mallory who gave Graves his love of literature and poetry in particular.

When war was declared in 1914, Graves gained a commission in the Royal Welch Fusiliers but spent the first few months looking after foreign soldiers in camp in Lancaster as his commander felt he was not yet ready for war. However, in May 1915 he was eventually sent to France and served with the 2nd Welsh Regiment. Graves commanded a platoon of forty men aged between 15 and 63. Two months later, he went on to the Royal Welch Fusiliers at Laventile where he recorded that the officers failed to take the war seriously and felt it was more important to keep up regimental traditions.

Graves’ first real experience of war was at the Battle of Loos, which he referred to as a “blood balls-up” after only five of the company officers survived. The poem ‘The Dead Fox Hunter, In Memory of Captain L. Samson’ was written about this battle.

In November 1915, Graves met Siegfried Sassoon at Locon, north of Cambrin. Sassoon went on to write about Graves in ‘Memoirs of an Infantry Soldier’, where the latter appeared as David Cromlech - a man who believed everyone should know his opinion and whose appearance was ‘deplorably untidy’. Despite this, Sassoon respected Graves and they discussed poetry at length while on the front line.

After leave, Graves returned to France on 27th June 1916 with the rank of captain. Although he arrived too late to take part in the Battle of the Somme, in the second week he was moved to the battlefield near Mametz Wood where the 38th Welsh Division had suffered numerous casualties. He was expected to camp near where the bodies lay in the battlefield, which he remarked was “a certain cure for the lust of blood”.

On 19th July, Graves was injured at High Wood when a German shell exploded and he was hit in the chest. Graves was given up for dead and only survived being buried as a war casualty when he was spotted breathing while being carried to the grave. His parents were even sent a letter informing them of his death, just one day after receiving a letter from Graves informing them he was recovering from his wounds. This incident is recalled in his poem “Escape”.

The wounds sustained by Graves left him unfit for duty and he was given leave and sent to Oxford University to work as an instructor in the University Officer Training Battalion. He met up with Sassoon during this time, just as the latter was publishing his “Wilful Defiance”. Graves decided to use his contacts to ensure that Sassoon was treated as someone who was suffering from psychological trauma rather than as someone who required court martialling.

While Graves was probably best known for “Goodbye To All That”, a book about his war time experiences, he also wrote many poems about the war that demonstrated a clear association between him and the men he led, including those who died. In 1916, he had published “Over the Brazier” and the following year “Fairies and Fusiliers”. Graves also went on to find fame for his autobiography and for “I Claudius” and “Claudius the God”.

Graves died in 1985.

MLA Citation/Reference

"Robert Graves". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.