The German Spring Offensive of 1918

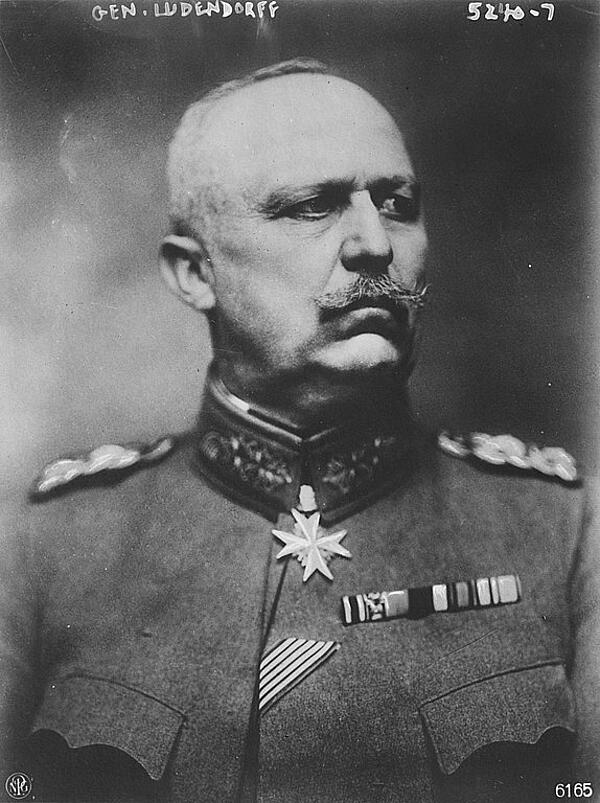

In the spring of 1918, Ludendorff ordered an enormous German attack on the Western Front, and the resulting Spring Offensive was Germany’s attempt at ending World War One.

After adding 500,000 troops to the Western Front from the Russian Front, Ludendorff was confident of success and felt assured they would defeat the Allies.

The Allies were aware that a major attack was on its way but they didn’t know where it would come. The British decided to reinforce their positions near the coast while the French felt it important to strengthen their lines south of the British troops. However, there was a weakness in the British line west of Cambrai. This was due to the unfinished trench system in the area, with those that had been dug proving inadequate.

Sir Hubert Gough, who commanded the Fifth Army in this area, was aware of the issue and was conscious that he had few reserves to call upon should the Germans strike in that region.

On 21st March 1918, Ludendorff launched the offensive and within just five hours the Germans had launched one million artillery shells at the British lines held by the Fifth Army. The bombardment was followed by an attack by elite storm troopers, who were skilled at delivering fast, hard attacks using weaponry such as flame throwers before moving to their next target.

By the end of the first day, 21,000 British soldiers had been taken prisoner and the Germans had made significant advances across the Fifth Army lines. Senior British commanders started to lose control of the situation, which was vastly different from the static trench warfare that had dominated the war until this point.

Gough made the decision to withdraw the Fifth Army and so secured for the Germans the biggest breakthrough they had seen in three years on the Western Front, even losing Britain the Somme where so many people had lost their lives in 1916.

The advance also made it possible for the Germans to use their Krupps cannons to shell Paris, which was 120km away from the front line. It took just 200 seconds for the shells to travel the distance and 183 shells landed in the capital.

The first few days of the attack had been so successful for the Germans that 24th March was declared by William II to be a national holiday, and many Germans began to assume the war was over.

However, the Germans now faced a large problem - to secure their rapid success they had been unable to carry much more than weapons. This meant their supply lines were seriously strained and the storm troopers were soon without any supplies at all.

The German 18th Army in particular had been very successful and had advanced to Amiens, now threatening to take the city. However, Ludendorff’s decision to advance them rather than to consolidate his troops and supplies meant that they were soon eating their own horses and their mobility was severely reduced.

As the Germans advanced to Amiens they went via Albert, where the Germans lost all sense of discipline and began to loot shops looking for food. The advance on Albert all but stopped and the attack on Amiens halted entirely.

Ludendorff, fearing that he had lost all control, was not helped by the fact that the German attack had also lost them 230,000 men.

Soon the American troops began to descend on the Western Front. By the end of March, 250,000 American soldiers had joined the conflict and the end was in sight.

Neither Ludendorff or Hindenburg were ready to face the reality of their situation. By June 1918, the German Army was seriously weakened and on 15th July Ludendorff ordered the last offensive the Germans would issue during World War One.

The offensive was a disaster. While they advanced two miles their losses were huge and the French allowed them to continue to ensure their supply lines were stretched too far. The French then hit back on the Marne and their counter-attack devastated the remaining army. Between March and July 1918, the Germans lost a total of one million men.

MLA Citation/Reference

"The German Spring Offensive of 1918". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.