Total War

‘Total war’ was a concept that was not introduced into the minds of the British until May 1915, and was set to last until November 1918. Total war put the whole country on a footing for compulsory war, which was controlled by the government.

World War One actually began in August 1914, but it was met with arguably a significant amount of naivety. Specifically, it was widely believed that the war would be over by Christmas so many young men actually volunteered to enlist in order to ensure they didn’t miss the ‘fun’ of battle before Germany surrendered.

Sadly, this belief was met with a sharp dose of reality when the brutal Battle of Marne took place, and despite the Allied win many soldiers were introduced to the horrors of trench warfare.

As the death toll rose and the stories from the trenches began to reach Britain, the number of volunteers began to reduce. However, in May 2015 the shell crisis - the shortage of artillery shells on the front line - the government began to struggle to equip men ready for ‘the big push’, so it became necessary to introduce the concept of ‘total war’.

By 1915, the war was not going well for the Allied nations and the predicted easy win over the ‘Hun’ was starting to look incredibly remote. Even politicians including David Lloyd George believed that victory would be harder to achieve than was initially assumed. Speaking to Colonel Maurice Hankey - secretary to the cabinet’s War Committee - as late as November 1916, he said: “We are going to lose this war”.

One of Britain’s biggest issues was that Prime Minister at the time, Herbert Asquith, was seen by many as not being suitable for leading the country during war time. He responded to concerns by setting up two committees - one for Dardanelles and one for administration. However, they were not given the powers they needed to allow them to be effective. As such, final decisions rested with the Cabinet and Lord Kitchener, who was Secretary of War.

One man who was not convinced about the government’s approach to the war was David Lloyd George who was Minister of Munitions (1915 - 1916) and took over the role of Secretary of War after Kitchener’s death. His more vigorous approach to ensured he was rated highly by many. However, he also struggled with a large group of politicians who questioned his motives. In a letter to Arthur Bonar Law, Asquith said: “He lacks the one thing needful - he does not inspire trust.”

Once Lloyd George was in office he made immediate changes - creating a small war office in a bid to make it a more effective unit that would allow him to work without having to go through his critics (including Sir William Robertson, chief of the General Staff). However, this approach was rejected by Asquith and Lloyd George was not well received and he made the decision to resign.

Lloyd George’s loss was not taken well by many of the members of the cabinet, including Liberal Democrats and Conservatives, who ultimately forced Asquith to resign as a result. Bonar Law was asked to form a government but he failed, and eventually on 6th December 1916 a government was formed by Lloyd George.

Once in power, his plans for a War Cabinet were immediately put into place, meeting 200 times in the first 235 days of its existence. The Cabinet took full responsibility for the war and on three occasions even became the Imperial War Cabinet, hosting prime ministers from the Dominions. The cabinet had the power to bypass the slow-moving government and provided the Prime Minister with accurate, up-to-date statistics that helped him address the war and the country. This date actually made it possible for the government to stay aware of the number of ships being sunk by Germany, as well as the amount of food production taking place in England, so ultimately made it possible for Lloyd George to ensure his country did not starve.

The War Cabinet also made it easier for the government to hold power of Britain during war time, although this was aided by DORA. Although trade disputes did occur (occasionally leading to strikes) they were often resolved easily as strikes were technically outlawed and the government had control of vital industries.

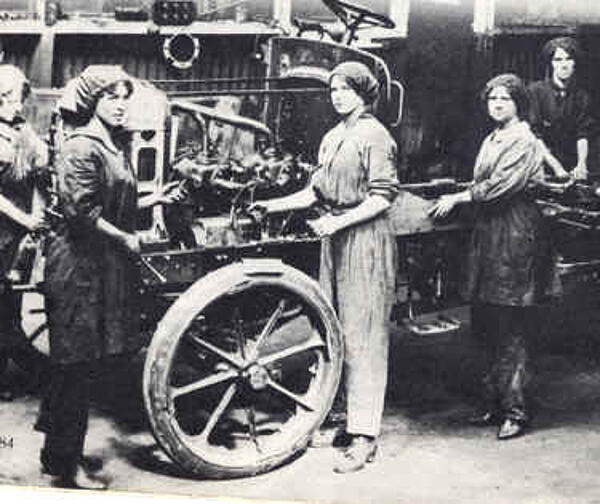

Some of the vital industries that were taken by the government included factories, which became national munitions factories, as well as railways and coalfields. For those working at the munitions factories in particular, the job was seen as so vital that they were well cared for, including having nurseries placed close by to ensure mothers could work while looking after their children. This was particularly important when conscription changed in May 1916 to include all men, even those who were married, between the ages of 18 and 41.

Despite their best efforts, the rationing was extended by 1918 to include other foods such as butter, eggs, sugar and meat, and in April 1918 the government took control of flour mills. However, that wasn’t the only extension introduced to deal with the war; the government extended tax to provide funding, raising it from 1s 8d to 6s per £1 to produce more than 10 times the pre-war level - a total of £2,579 million.

Although Lloyd George never achieved a strong relationship with the military, he did play a vital role in keeping Great Britain fed and strong in battle during the war, and is credited for having played a significant role in the outcome. Total war ultimately made it necessary for the government to be involved in most aspects of the country during war time, but it also led to success.

MLA Citation/Reference

"Total War". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.