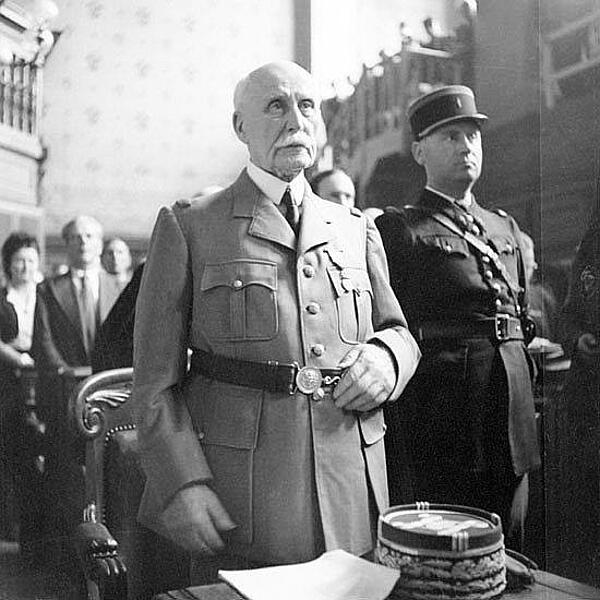

Marshal Philippe Pétain

Philippe Pétain was born in 1856 in Cauchy-à-la-Tour near St. Omer, France. He was educated at Dominican college in Arceuil before he joined the infantry in 1878.

Pétain followed the normal career path of an officer; he worked hard in his post and by 1906 he was teaching at École de Guerre. In 1912, Pétain was promoted to colonel and then, just before the war began, he was named general.

It didn’t take long for Pétain to gain a reputation and he was soon respected as a man who would take care of his soldiers. As such, when he was asked to command the French Second Army at Verdun his placement was well received - particularly as the battle was already resulting in severe casualties on both sides.

While neither side emerged victorious, the French side did consider the battle a victory as Germany and failed in their plan to take the city, and the forts, and so Pétain received much praise for his success.

In April 1917, the French army mutinied for four months leading to 600 men being sentenced to death as a result. However, only 43 were actually executed. Following the mutiny, the French government was determined to get the soldiers back on board and appointed Pétain commander-in-chief of the French army as a means to achieving this. Part of Pétain’s job was to used his natural policies of healing and care to build morale. However, Pétain’s reputation was such that his mere promotion to commander-in-chief had a huge impact on the level of positivity among the soldiers.

In December 1918, Pétain’s successes in the war were rewarded with his promotion to Marshal and given his baton at Metz. However, the end of the war was by no means the end of his career. Between 1925 and 1926, he commanded French forces as they defeated Abd-el-Krim in Morocco, and in 1929 he was further promoted to Inspector-General of the Army, as well as being asked to serve as Minister for War in 1934.

Following his eventual retirement, he pursued his interest in politics and became the first French ambassador to Franco’s Spain in 1939. However, he was called back to France in 1940 and appointed Prime Minister, just as Nazi Germany appeared to be gaining the upper hand. On 22 June 1940, Pétain concluded an armistice with the Germans - but this action literally split France in two. Under its terms, Germany ran the territory they had occupied during the invasion following Blitzkrieg, while the other hand was run by the National Assembly Government under Pétain in preparation for when Germany would fully occupy France, in November 1942.

In July 1940, The National Assembly gave Pétain the right to rule by authoritarian methods in order to rid his side of France of its “moral decadence”, with the police subsequently given the right to round up anyone who was considered to be decadent. The police also helped Germany round up Jews to be sent to death camps. To many, it appeared that there was a police state in both sides of France, not just the side run by the Germans.

Following the success of the Allies on D-Day in June 1944, Pétain was take with the retreating German army and in July 1945 he was put on trial for treason. He was found guilty and stripped of his rank of marshal. He was sentenced to death but this was later reduced to life imprisonment on the Île de d’Yeu in the Bay of Biscay. In 1951, he died at the prison and, as a result of his treason, his wish to be buried at Verdun where he had seen such great military success was ignored.

MLA Citation/Reference

"Marshal Philippe Pétain". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.