America and World War One

America entered World War One on 6 April 1917. Until then, President Wilson had tried to keep out of the war, but for a variety of reasons this stance became untenable. Push factors included public sympathy for the allied cause; the sinking of the Lusitania; news of German atrocities and the threat to international trade. The last straw was Germany’s introduction of unrestricted submarine warfare on 9 January 1917. All of these factors caused Woodrow Wilson to ask Congress to declare war on Germany.

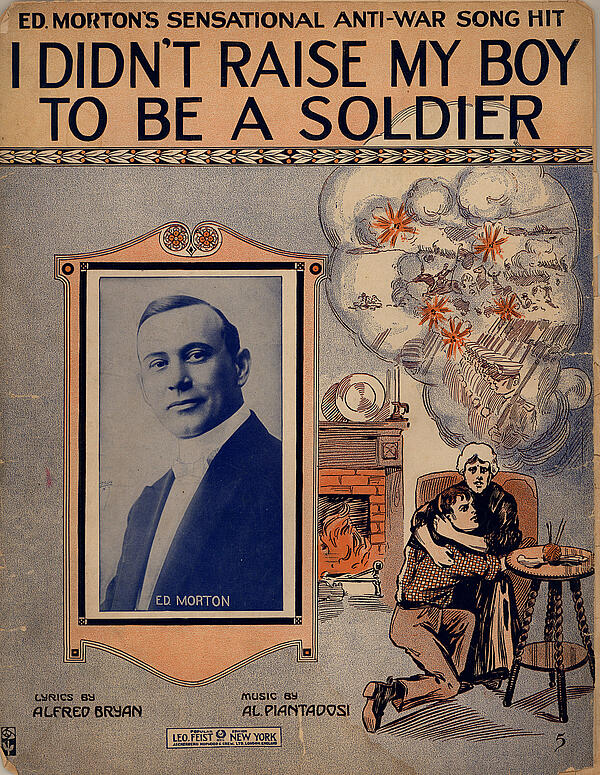

At the beginning of World War One America adopted a policy of neutrality and isolation. The news of trench warfare confirmed to the government that they had adopted the right approach. The majority of Americans supported this stance - the fact that Europe had descended into such a bloody conflict shocked them.

There were some groups within America who supported involvement in the war, including American-Germans and American-French citizens, However, the majority of Americans were desperate to stay out. The success of Wilson’s re-election campaign in 1916, with his slogan of “he kept us out of the war”, is evidence of this.

Woodrow Wilson was in full control of foreign policy. As a student of modern history, he understood that the causes of this European war were complicated. However, as long as America’s interests remained unthreatened by the conflict he would maintain her neutrality.

On 4 August 1914, Wilson officially announced that America would be neutral in World War One. That neutrality extended to a policy of ‘fairness’ – meaning that American bankers could lend money to both sides in the war. Overseas trade was more complicated. Trade with both sides was permitted and merchant ships crossed the Atlantic to trade. However, a British naval blockade of the German coastline made it all but impossible for America to trade with Germany. The British policy of blockading Germany was the primary reason for Germany ultimately introducing unrestricted submarine warfare. Germany argued that Britain forced her into taking this action.

Germany’s use of U-boats was the primary reason America declared war.

On 4 February 1914, Germany announced that any merchant ship operating in a specified zone around Britain would be legitimate targets. They made no exceptions for neutral ships after Allied ships had taken to flying the flag of neutral nations to ensure their safety. Wilson warned the Germans that he would hold them to account if any American ships were sunk. The sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1914 tested this threat; 128 Americans were killed in the tragedy and Britain hoped that it would prompt America to join the war. Wilson was outraged and responded by sending four diplomatic protests to Germany. However, the 'Lusitania' was not an American ship and Wilson accepted the Germans’ change of policy - that U-boats would adopt 'cruiser' tactics and surface and attack a ship by guns fitted on to their decks. Germany also agreed to give compensation for any American ships that were destroyed, including the value of their cargo.

By the end of 1915 America’s relationship with Germany had reached a tolerable balance. On 2 February 1916, the House-Grey Memorandum was drafted by Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, which established that if Germany rejected American intervention, the United States would likely join the war. Although this appears to be a jump from America’s policy of neutrality, Colonel Edward House had not gained WIlson’s approval. Moreover, the British government vetoed the memorandum. By mid-1916, the Americans seemed to have developed a more positive relationship with Germany.

The same was not true with regards to Britain. First, Britain turned its back on the Memorandum. Then Britain increased its maritime activities with regards to stopping ships trading with Germany and other members of the Central Powers. Finally, the treatment of those arrested after the failed Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916 had greatly angered the influential Irish-American community on America's east coast. To many, Britain had lost the moral high ground and to some it seemed as if Britain did not want peace at all.

On 7 November 1916 Wilson won the presidential election. His victory was largely due to his promise of peace for America. In comparison, his opponent Charles Evans Hughes was seen as a warmonger. Wilson spent the next few months trying to establish a way in which America could lead peace negotiations that would end the war. He asked both sides what it would take to end the war. Britain and France sent back replies that stated their terms - terms that could only be met with a decisive military victory. Germany's reply was vague and evasive.

Regardless of this, Wilson continued to fight for peace based around the idea of a League of Nations. In mid-January 1917, he set up secret negotiations with both Britain and Germany to obtain their agreement for America's mediation in a peace plan. Wilson had a very clear idea of what he wanted:

"Peace had to be a peace of reconciliation, a peace without victory, for a victor's peace would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently, but only as upon quicksand."

America played a vital role in the allied victory. The US mobilised over 4 million troops and their arrival on the frontline boosted morale and strengthened the Allie’s strategic position. Just over 116,000 American troops were killed in the war.

MLA Citation/Reference

"America and World War One". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.