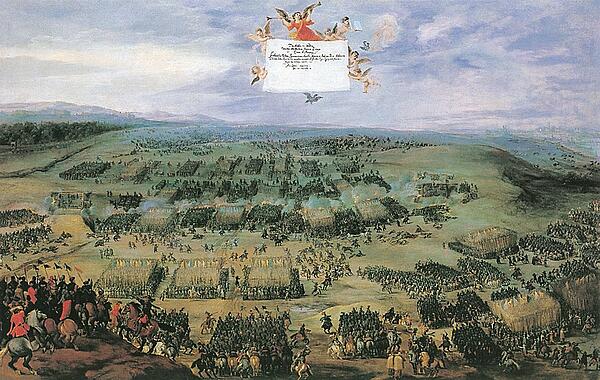

The Thirty Years War 1621 to 1626

The Thirty Years War is considered to be one of the most destructive wars in human history, responsible for the deaths of millions both directly and indirectly. Many historians argue that the most devastating and aggressive periods of the war took place between 1621 and 1626, when violence began to spread across Europe.

In Eastern Europe, Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II found himself in a strong position, but his success had began to concern leaders in the west. This was mainly due to the fact that Ferdinand was renowned for being a hard-line Catholic with desires to impose his authority across the Empire.

In France, leaders were particularly concerned that his ambitions for expansion could lead him right up to the French border, while the United Provinces felt Spain could also benefit hugely from the new prestige of the Holy Roman Empire.

1621

In January 1621, Ferdinand II made the decision to impose the Ban of the Empire on Frederick of the Palatinate, which rendered the latter a ‘persona non grata’ or unwelcome in the Holy Roman Empire. Frederick, who was a senior Elector, was subsequently outcast and Maximilian was ordered to take his place - a reward for his actions in supporting Ferdinand during the Bohemian crisis.

Ferdinand’s actions angered the German princes, who began to rally around in opposition of his treatment of the state. So much so, in fact, that in February the princes and German free cities of the Protestant Union met at Heilbron to deliver formal protest. Sadly for them, Ferdinand responded by ordering them to disband their army.

By May, the princes and free cities relinquished and decided to disband their military presence under the Mainz Accord, formally dissolving the Protestant Union. However, there were three princes who refused to sign the Mainz Accord: the Margrave of Baden, Duke Christian of Brunswick and the Count von Mansfeld. Although none of these princes were particularly significant in terms of the Holy Roman Empire, they took over the remaining unruly mercenaries who made up the Protestant Union army.

1622

In 1622, Count von Mansfeld fought in a series of campaigns against the Count of Tilly, commander of the Catholic League’s forces and defeated the victor at White Mountain at the Battle of Wiesloch by April. However, he soon suffered defeats of his own Wimpfen and Hö chst. Soon, the Catholic army occupied the Electoral lands on the right bank of the Rhine, while Spain had taken the left bank, leaving the position of the rebellious Princes looking bleak. Subsequently, the cities of Heidelberg and Mannheim also fell to Tilly.

1623

Once these territories had been taken by the Holy Roman Empire, Maximilian was given control of them and quickly reimposed Catholicism, expelling all Calvinist ministers. By February 1623, the Electoral title of the Palatinate was officially given to him by Ferdinand during a meeting of the Electors at Regensburg. Additionally, John George of Saxony was gifted Lusatia and George William of Brandenburg was given East Prussia.

As a result of this, the Catholics had a give to two voting majority for the position of King of the Romans - including three Catholic archbishops and two votes held by Maximilian - ad that this would save Catholicism in Germany.

England

Following Charles at Madrid and the blow of a defeat for the Duke of Brunswick at the Battle of Stadtlohn in 1623, Mansfield decided to turn to England for aid. James I responded by granting permission for an army of 12,000 English men to be ‘donated’ to the cause, in a move that would significantly increase England’s involvement in an already complex political situation.

France

France remained suspicious of Ferdinand, refusing to accept that whatever was good for Habsburgs was good for Catholicism as a whole. A Habsburg power in Germany was too close for France but internal issues concerning Huguenots prevented them from being involved in issues in Germany until 1622 - when the Treaty of Montpellier began to ease issues within France itself.

France - having never accepted its expulsion from Italy during the Habsburg-Valois War - was determined to regain its position. However, this was altered by any Spanish position in the Valtelline.

The Treaty of Madrid - signed in 1621 - had aimed to provide Protestants in the Valtelline with some rights but the Catholics in the area had failed to adhere to the treaty. In fact, in 1622 they had overturned the Grisons power and left the Spanish Road open for the Habsburg to use. In 1623, France signed the Treaty of Paris with Savoy and Venice, which fed off growing anti-Catholicism in the area and sought to eject Spanish troops from the Valtelline and prevent this from continuing.

1624

The Paris Treaty was arguably a good sign that conflict between France and Spain was likely to develop further, and in 1624 the Spanish asked Urban VIII to provide protection. This resulted in Papal troops being sent to Spanish forts along the pass granting temporary calm in the area, but it wasn’t long until Cardinal Richelieu returned to favour and decided he wanted to restore royal authority in France.

1625

Cardinal Richelieu decided to take on the Habsburg and in 1625 he sent French troops - as well as Swiss Protestant troops - to drive out the Papal garrisons and close the pass.

The year 1624 had previously led to the signing of the Treaty of Compiegne between England, France and the Dutch, which symbolised their decision to stand up against Spain. However, in 1625 Spinola, one of Spain’s most senior generals, launched an attack, resulting in the fall of Breda in June.

However, by December 1625, England, Denmark, the Dutch and the Lower Saxon Circle had decided to form a coalition called the Coalition of the Hague, which had also gained support from Frederick of the Palatinate. The coalition made plans for a triple threat attack on the Habsburg and it wasn’t long before the Danish War of 1626 to 1629 broke out.

MLA Citation/Reference

"The Thirty Years War 1621 to 1626". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.