The Women's Social and Political Union

The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was founded in Manchester in October 1903. The WSPU campaigned for social reform through protests such as hunger strikes and property damage. Its militant stance is summed up in its slogan: “Deeds, not words”.

The Manchester Women's Suffrage Committee (NESWS), founded by Linda Becker, was the predecessor to the WSPU. Women who backed women’s right had traditionally put their faith in local trade unions the Independent Labour Party (ILP). The objective of the ILP was "to secure the collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". This included rights for women.

However, Emmeline Pankhurst called for a greater commitment to women’s rights from the Labour Party. As a result, the principal objective of the Women’s Social and Political Union was to put pressure on the Independent Labour Party. This was made easier by the fact that a number of members were married to ILP members. From the beginning the WSPU sought to live by its motto: "Deeds, not words".

The WSPU did not begin its life as militant movement, but it became gradually more and more militant as members grew frustrated with the government.

When Asquith’s Liberal Party came to power in 1906, the WSPU were hopeful that because of its liberal agenda, the Party would pioneer for political rights for women. When this did not happen, the WSPU resorted to militancy.

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney brought attention to the cause in 1905 when they disrupted addresses by the most prominent Liberals of the day - Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey. Heckling was frowned upon during political speeches, however, Pankhurst and Kenney bombarded the politicians with questions. They wanted to know Churchill’s and Grey’s stance on women’s rights.

These actions, and others like it, were so shocking because they broke social conventions - women traditionally did not interfere with politics, which was seen as a “man’s world”. Secondly, their actions at the meeting were seen as damaging to the reputation of women seeking political equality in more reserved ways.

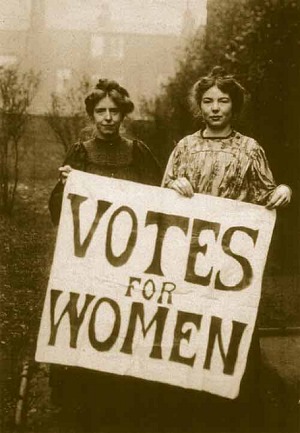

Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were arrested for unfurling a sign which read “Votes for Women”. When they refused to pay a fine they were sent to prison. The trial created much interest in the movement, and membership of the WSPU increased as a result.

In 1906 the Liberal Party came to power. It was strongly believed that they would support the campaign for women’s right to vote. However when this proved not to be the case the WSPU began to turn to increasingly militant tactics in order to raise awareness. Acts of disobedience continued and more arrests followed. The Suffragettes, as they had now become known, were becoming increasingly bold, militant, and their campaigning more widespread. However, there was still little advancement in voting rights for women.

Militancy set the WSPU apart from other female movements and some women criticised their radical actions. This alienated some women from the movement. Many working class women were shocked by militant tactics and they turned their backs on movements like the WSPU. The WSPU became the preserve of militant feminists. Therefore, the group lost its much needed popular support. The alienation of the working class explains why the WSPU never became a mass movement.

THe objectives of the WSPU also held it back from achieving widespread support. It was believed that the group was fighting for political equality rather than for complete social and professional equality. To many working class women the slogan "Votes for Women" did not answer their social problems.

The historian Sandra Holton argues that the WSPU lost sight of what its initial objectives, with some fighting for only political equality and others advocating full adult political suffrage regardless of gender.

The militant action of the Women’s Social and Political Union fell into three distinct phases:

- 1905 to 1908: political meetings were disrupted.

- 1908 to 1913: the WSPU became more militant in its protests and hunger strikes became a popular tactic.

- 1913 to 1914: the WSPU increasingly carried out attacks on the personal property of those opposed to women’s suffrage.

When the war broke out in August 1914, the WSPU called a halt to its activities and called on its members to support the government in the War effort. The First World War saw women entering the labour market in unprecedented numbers and in sectors that were previously almost exclusively male.

See also: Sylvia Pankhurst

MLA Citation/Reference

"The Women's Social and Political Union". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.