The Children's Crusade

The Children’s Crusade is considered one of the more unusual events to take place in Medieval England, and many aspects are difficult to define as a result of the myths surrounding it.

The Children’s Crusade followed the Fourth Crusade, which took place between 1202 and 1204, occurring eight years afterwards. A failure, the Fourth Crusade had not even seen the crusaders reach the Holy Land as a result of being more concerned with plundering, as witness in the Sack of Constantinople.

However, the lack of long-term success by the crusaders and not damaged the believe that Jerusalem should be recaptured by the Christians.

In 1212, a group of crusaders set of from France and embarked upon a crusade to the Holy Land (and by some accounts another set off from Germany in a move known as Nicolas’s Crusade). It was not considered particularly unusual for this group to have set off on a crusade as many had already done so before them. However, accessing to the narrative, this group was particularly unusual as it was composed almost entirely of children and youths. According to historians, these children were all aware or persuaded of the common Christian belief that the Holy Land was rightly theirs, and they were convinced that it was their responsibility to retake the city under the protection of God.

There are very few facts about the Children’s Crusade that are indisputable, and many believe it to be a romantic myth. However, regardless of the age of those who travelled, it is commonly agreed that this crusade was not short of a disaster.

The story begins wth a boy called Stephen of Cloyes, who was a shepherd born around 1200. This would make him just 12 years old at the time of the Children’s Crusade. Little is known about Stephen, but it is doubtful being a peasant that he was able to read or write, and all his experience of life would have be related to the farm where he worked.

However, in May 1212 it is said that he made his way to the court of the King Philip of France and demanded an audience with the king. Appearing in front of Philip, Stephen it said to have presented him with a letter reportedly given to him by Christ in a guise as a poor pilgrim, which ordered the boy to organise a crusade and capture Jerusalem. Unsurprisingly, the king was unimpressed by his plight and ordered him to leave.

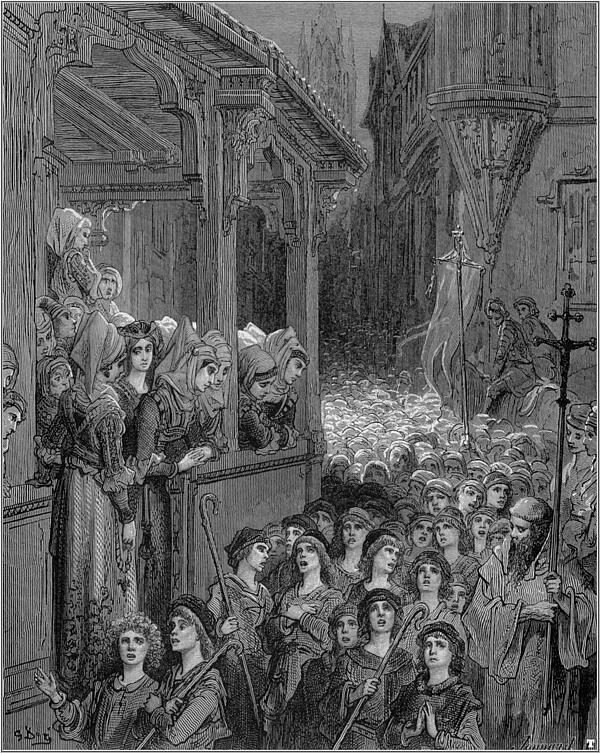

Stephen was undeterred by the response, taking to the streets and preaching to children about the message from Jesus and stating that they should fulfil their duty and accompany him to the Holy Land. As a result, it’s believed that a large group of boys and girls marched through castles, villages, towns and cities carrying crosses, banners and candles. During their march, they were singing songs including “Lord God, Exalt Christianity! Lord God, Restore us the True Cross!”

When asked how he would cross the Mediterranean, Stephen replied that it would be simple as they would walk across with the help of God, who would be protecting them.

By June 1212, the narrative suggested that Stephen had 30,000 followers, all of them children or youths. Despite doubts that the story is correct, there have been around 60 descriptions of this discovered from the late13th Century, with around 16 of those believable, at least in parts, in the eyes of notable chronicler Matthew Paris. These accounts were also included in the writings of sober Victorian historians, although it’s now believed that they didn’t follow the normal critical methods of describing such events, and were influenced by the romantic notion of the story. In fact, modern historians now believe that the army was made up mainly of wandering poor and dispossessed.

The crusade was never sanctioned by the Roman Catholic Church, who purportedly believed it was doomed to failure. However, this seemingly did not deter the children. Questions have since been asked about why the Church did not stop the event, but some argue that the Church believed the actions may shame the kings and emperors into launching another crusade themselves.

Sadly, the Children’s Crusade was as much of a failure as had been predicted. The distances walked were too far for the children, and many failed to even make it half way before dropping out or dying between Vendome and Marseilles. Additionally, Stephen’s prophecy regarding the Mediterranean Sea also did not come to pass, and the remaining children were forced to cross by boats from Marseille. Sadly, that was the last time the children were ever seen.

However, many years later a priest returning from travel around northern Africa claimed to have met some of the surviving children as adults, and claimed that only two of the seven ships had sunk, while the other five had been captured by pirates and the children sold into slavery - they would have been particularly valuable in Algeria and Egypt being from Europe.

There is no proof that any of these accounts were true as none of the children who left Marseilles ever returned to their homes. As a result, it’s impossible to know what happened to those who did take part in the Children’s Crusade.

Nicolas's Crusade

There have also been accounts of a German Children’s Crusade taking place in 1212. This was purportedly led by a child called Nicolas, who said he had 20,000 followers. He was thought to have the same dream as Stephen, and planned to take Jerusalem back from the Muslims.

Nicolas’ crusade also included religious men and unmarried women, so it was not fully considered a Children’s Crusade. Despite that, their dangerous journey across the Alps led to many dying from cold, including the adults. However, those who made it across pushed onto Italy.

Having arrived in Rome, the remaining crusaders met with the pope who praised their bravery. However, he told them that they were too young to be successful in such a venture and sent them back to Germany. Sadly, many of them did not survive the journey back, while a group who boarded a ship in the Italian port of Pisa bound for the Hold Land were never heard from again.

Although both Children’s Crusades were a disaster, historians argue that they do highlight the importance of religion and Jerusalem in particular to everyday people living in the Middle Ages.

See also: The Fourth Crusade and The Fifth Crusade

Further reading: The Children's Crusade, Dana C. Munro

The American Historical Review

Vol. 19, No. 3 (Apr., 1914), pp. 516-524

MLA Citation/Reference

"The Children's Crusade". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.