Canals 1750 to 1900

The Industrial Revolution needed canals - man-made rivers - to move the large quantities of heavy goods that had been produced. The weight made it is virtually impossible to transport these goods by road, so over water was the easiest way.

The Duke of Bridgewater, fittingly for his name, his commonly associated with the early canals in Britain. The duke owned coal mines in Lancashire - he would sell the coal in Manchester, six miles away, so need a method of getting his coal from the mine to the market. He entrusted the job of finding a solution to this problem to engineer James Brindley, despite the fact he had no previous knowledge of building canals. The Duke of Bridgewater borrowed £25,000 to fund the project, which in those days was a huge sum of money.

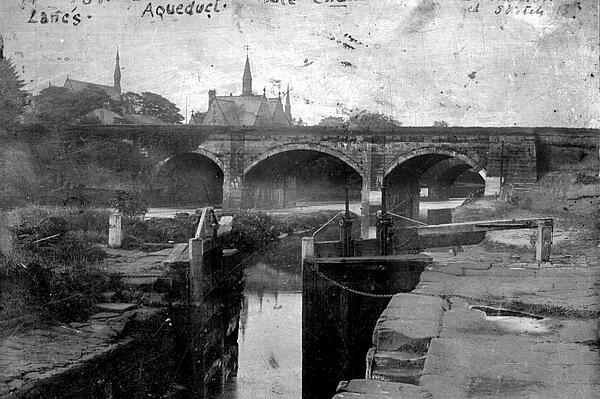

In 1761, two years after the project began, the canal was complete, with a network of tunnels now linking the coal mines. Despite the heavy costs of creating the canal, it proved to be a great success and the duke quickly made his money back - this started the trend of people building canals, particularly around Manchester and Liverpool.

The engineer behind it, Brindley, also gained fame for his work on the early canals and he would go on to build nearly 400 miles of the waterways.

Two of the biggest challenges he faced was making sure the canals were flat, so the water would not simply run away, and also ensuring the canals were waterproof. He used a clay mixture to line the paths he created before filling them with water while he planned to routes of the canals to avoid hilly areas.

Canal mania struck at the end of the 18th century, with people rushing to invest in and build the water highways of Britain. Nearly 4,500 miles of canals had been built in Britain by 1840, but this method of transport was to witness a decline over the next century, because:

- Canals varied in size depending on the engineer, which meant only certain barges could travel down certain canals

- Roads improved

- Quickly perishing foods could not travel down the slower or longer canals

- The water would freeze in winter

- The development of the railways

See also: Roads 1750 to 1900

MLA Citation/Reference

"Canals 1750 to 1900". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.