Freedom Ride

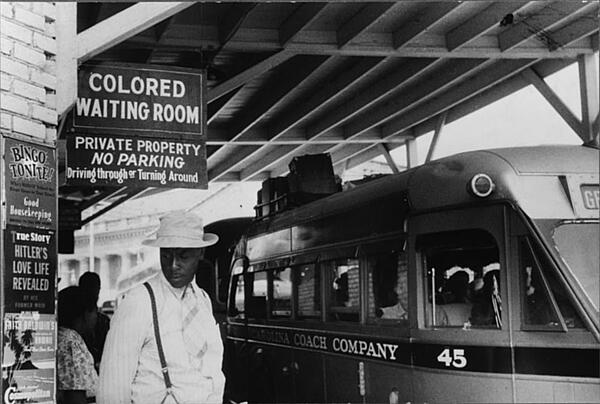

The 1961 Freedom Rides saw African American and white civil rights activists challenge segregation on interstate transport. The activists were faced with extreme violence as they travelled across the South, but their resilience led to the nationwide prohibition of segregation in bus and train stations.

In federal law, the segregation of interstate buses was already illegal. In 1946, the Supreme Court had ruled segregated seating on interstate transport as unconstitutional. However, for this to be enforced it had to be accepted on a state and local level. The 1946 ruling was met by resistance in the South, thus, it proved ineffective.

To enforce this new ruling, the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) planned a “Journey of Reconciliation” through the South in 1947. The Upper Southern states reacted to this violence - it was seen as challenge to the white superiority that defined the South. Some of the members were even arrested and punished by being forced to work in chain gangs. Faced with the constant threat of violence, the “Journey of Reconciliation broke down. However, it did provide the inspiration for the 1961 Freedom Rides.

In 1961, civil rights activists challenged the 1960 Boynton v. Virginia ruling. The Supreme Court decision found segregation of all interstate transportation facilities to be unconstitutional. CORE recruited activists to test the effectiveness of this ruling.

The plan was similar to the “Journey of Reconciliation”, except this time female activists would be recruited too. The white volunteers would sit in black-only seats while the black demonstrators would sit in the white-only sections.They also challenged the segregation of restrooms and waiting areas.

CORE director James Farmer argued for the objectives of the Freedom Riders by explaining that they were merely enforcing the law that was created by the Supreme Court.

Before leaving on the Freedom Ride, the activist John Lewis said:

"I'm a senior at American Baptist Theological Seminary, and hope to graduate in June. I know that an education is important, and I hope to get one. But at this time, human dignity is the most important thing in my life. That justice and freedom might come to the Deep South."

The original group of 13 Freedom Riders left Washington DC on 4 May 1961. The plan was to reach New Orleans on 17 May to celebrate the anniversary of the Brown v Board of Education ruling.

While the Freedom Ride in the Upper South was met with little resistance, in the Deep South it was a different story. In particular, Bull Connor, the police chief of Alabama strongly opposed the rides.

As 14 May was Mother’s Day, Connor had given the city police the day off. However, he was also aware that the Freedom Ride would pass through the city that day, meaning that any violence against them would not be polices. When a mob attacked the Riders, Connor claimed to know nothing about it.

By the time they reached Birmingham, the Freedom Riders were going in different directions, with one group going to Anniston, Alabama. A mob of 200 people attacked those who arrived at Anniston. The bus was able to escape from the town but it was firebombed six miles from the town.

The members of the Freedom Rides were still committed to continue with their journey, but the bus company were worried they were would lose even more buses and the drivers were afraid for their own safety. However, by this time the Freedom Rides has gained considerable media attention so the Freedom Riders decided to continue their journey by plane.

At this point, demonstrators in the Nashville sit-ins picked up where the earlier riders had left off - theyargued that that those who opposed the civil rights movement would take the students’ retreat as a victory. In Birmingham, the Nashville students tried to convince a bus company to let them use a bus, but they were arrested and taken back to Alabama. The students remained determined to return to Birmingham, regardless of the resistance they faced.

By this time, Robert Kennedy, the Attorney-General had started to take notice of the rides. He pressured the Greyhound Bus Company to transport the Riders and the company agreed. The students were also given protection by Alabama’s state highway patrolman who agreed to station patrol cars along the 90 mile route from Birmigham to Montgomery.

The police escort left the bus just before arriving at Montgomery. A white mob used the opportunity to attack the Riders. They beat the Freedom Riders with baseball bats and iron pipes.Wwhite Freedom Riders were singled out for particularly brutal beatings. Reporters and news photographers were attacked first and their cameras destroyed, but one reporter took a photo later of Jim Zwerg in the hospital, showing how he was beaten and bruised. Seigenthaler, a Justice Department official, was beaten and left unconscious lying in the street. Ambulances refused to take the wounded to the hospital. Local blacks rescued them, and a number of the Freedom Riders were hospitalised.

In response to the mob violent, Robert Kennedy ordered 600 federal marshals to the city.

The following evening in Montgomery, Martin Luther King spoke to a meeting of 1,000 supporters of the Freedom Rides. However, the church was soon surrounded by a mob of 2,000. Robert Kennedy raised the issue with Alabama's Governor Patterson, who called in the National Guard who used teargas on the mob.

On 24 May 1961, a group of Freedom Riders left Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi. In Jackson the Riders were met with supporters rather than an angry mob. However, they were arrested for using the white section in the city’s bus station. The Riders were sentenced to 30 days in a state penitentiary in Parchman after refusing to ‘obey’ a police officer. The arrests only served to encourage hundreds more Freedom Riders to take up the cause.

The Freedom Riders never reached New Orleans but their demonstrations had been a success. The violent resistance in the South had gained national coverage and had involved the Attorney-General. The Interstate Commerce Commission introduced a strict ruling pushing the integration of public transport which came into force on 1 November 1961.

Writing on the Freedom Rides, historian Raymond Arsenault argued that this form of protest was so successful because it challenged the basis of Southern life:

“It was all-encompassing; this so-called Southern way of life would and not allow for any breaks. It was a system that was only as strong, the white Southerners thought, as its weakest link. So you couldn't allow people even to sit together on the front of a bus, something that really shouldn't have threatened anyone. But it did. It threatened their sense of the wholeness, the sanctity of what they saw as an age-old tradition.”

See also: James Meredith

MLA Citation/Reference

"Freedom Ride". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.