Education and Civil Rights

The relationship between education and civil rights was pivotal - the right to an equal education was a fundamental right, and one which was at the heart of the Civil Rights Movement. Some of the greatest opposition came from those who fought against desegregation in schools; whilst some of the greatest successes came in fighting for the right to education. The Brown v Board of Education decision and the Little Rock High School affair of 1957 were both landmark moments in the Civil Rights movement.

The collapse of Reconstruction allowed racial segregation to spread through the South. The legality of state laws that disenfranchised and segregated blacks was supported by the 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessey v Ferguson. It advocated the legal doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ - a concept that would be used to legitimise segregation in all aspects of public life, including education.

However, while schools throughout America were separate, they were never equal. In part, this was because education was seen as dangerous. Without a good education, African Americans had little chance to improve their prospects.

World War Two generated a greater demand for equality. A black Corporal in the US Army described his desire for change:

"I spent four years in the army to free a bunch of Dutchmen and Frenchmen, and I’m hanged if I’m going to let the Alabama version of the Germans kick me around when I get home. No sirreee-bob! I went into the army a nigger; I’m comin’ out a man."

In 1930, the NAACP employed Nathan Margold to produce a legal plan against segregation. The Marigold Report proposed to attack the doctrine of separate but equal by challenging the inherent inequality of segregation in publicly funded primary and secondary schools.

NAACP’s strategy was to take various cases of racial discrimination in education to the Supreme Court. Judgements that supported the civil rights of the student would then become legal precedent. This created the legal foundations for dismantling segregation.

NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall worked tirelessly to challenge segregation in education. Having been rejected by the University of Maryland Law School on racial grounds, he was determined to dismantle the “separate but equal” doctrine.

In 1950, Marshall declared that complete elimination of segregation in schools was the next objective. Marshall knew that challenges at a local level were integral to achieving this goal.

Five separate NAACP sponsored cases were brought together in the famous case of Brown v Board of Education of 1954. These included Brown itself, Briggs v Elliott, Davis v County School Board of Prince Edward County, Gebhart v Belton, and Bolling v Sharpe.

In 1952, these cases were brought the Supreme Court. The defending lawyers of segregation claimed that the states had already started work to improve black facilities. They also argued that these were state matters and not the concern of the Supreme Court.

Thurgood Marshall organised the plaintiffs who would be challenging segregation. He argued that integrated schools were a fundamental right for all Americans. The Supreme Court judge, Earl Warren, delivered the Court’s decision on 17 May 1954. Segregated schools were declared unconstitutional. The Court ordered the the desegregation of education with “deliberate speed”.

Despite this landmark decision, segregation persisted. The South resisted the decision and any attempts to enforce the law were met with violence. In Virginia, US Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. launched a campaign of ‘Massive Resistance’, which united white politicians and leaders in the state to resist the decision.

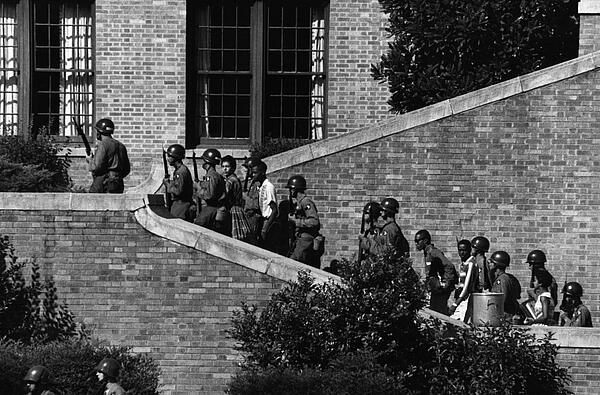

The case of Little Rock Central High School epitomises this resistance. In 1957, after pressure from federal government, Little Rock High School was to enroll its first cohort of African American students.

The students were met with violence on the first day of school. This resistance was only partially resolved after the involvement of Federal Government. It was a clear illustration of the Jim Crow mentality that continued to survive in the South.

Gradually, schools across America were desegregated. However, by 1962, whites-only schools still existed in Mississippi, South Carolina and Alabama.

By 1964, less than two per cent of African American children attended multi-racial schools in the 11 states associated with the south. Many colleges remained whites-only and these colleges had very few if any African American teachers on their staff.

Institutionalised racism was still very apparent in the North as well. By 1968, more than 30 per cent of all African American children went to public schools that were 90 per cent non-white.

By the 1970s, the South had become the nation's most integrated region. In 1976, 45.1 percent of African American students were attending majority white schools, compared with just 27.5 per cent in the Northeast and 29.7 percent in the Midwest.

See also: The 1957 Civil Rights Act

MLA Citation/Reference

"Education and Civil Rights". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.