Code-breaking is one of the most evocative images we have of World War II, thanks to stories frequently retold about the deciphering of the Enigma code and other covert operations at Bletchley Park.

Of the stories told about World War I, however, code-breaking does not feature so prominently. According to author Joseph A. Williams, however, the Great War’s code-breakers were no less exciting or interesting than their later counterparts.

Williams has told the story of one such operative in his latest book – “The Sunken Gold” – which tells the tale of a crack team of deep-sea divers who took part in operations that allowed for the cracking of some of the war’s most devious codes.

In 1918, Rear Admiral William Reginald “Blinker” Hall, top dog at Britain’s Naval Intelligence Division (NID), spearheaded an initiative to get hold of new intelligence material.

NID’s central role in the War was to crack codes pertaining to classified communications sent among Imperial Germany’s troops. Messages were almost always ciphered: encrypted in numbers, letters and other symbols that rendered the messages unreadable by a third party unless they knew the code.

Blinker Hall’s team could crack anything given time, but the best work was done by a network of agents hidden undercover throughout Germany’s forces that meant, realistically, that some orders or communications could be relayed back to British forces at near-instant speeds. It was the NID that deciphered the famous Zimmerman telegram, in which Germany offered an alliance to Mexico if war broke out with the US, which dragged the Americans into the war in 1918.

One of Hall’s most important operatives was a clerical worker in the Imperial German Navy offices who would feed codes directly to NID. He disappeared in 1918 without a trace, however, prompting the Admiral to look elsewhere for answers.

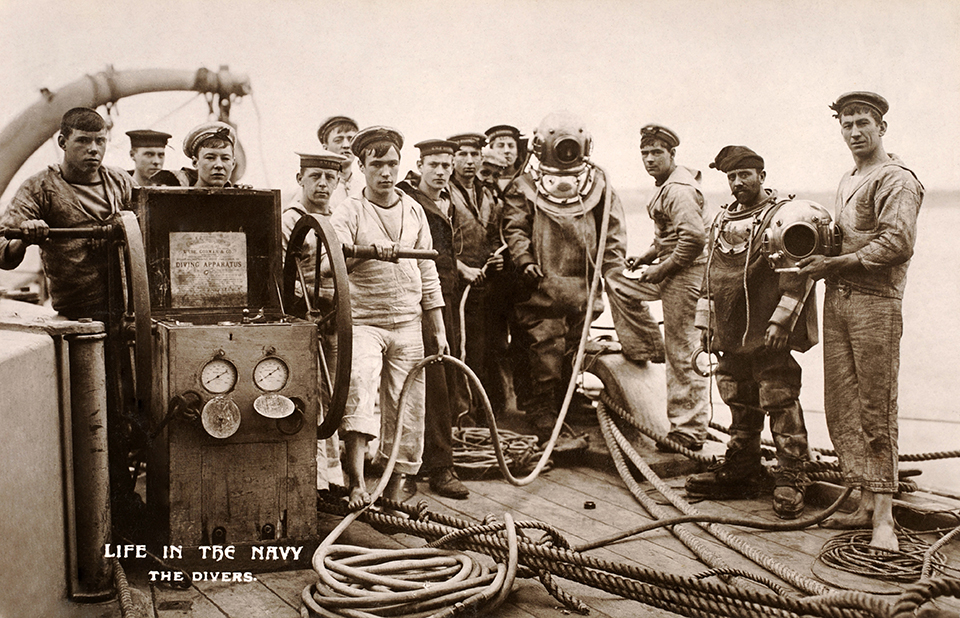

Hall commissioned Lieutenant Commander Guybon Chesney Castell Damant, a 36-year-old gunnery officer from the Isle of Wight, for a unique mission: to command a crack team of five divers who could obtain German codes from a sunk U-Boat. Damant, a deep sea expert, had successfully helped to recover 44 tons of gold bullion that sunk on the HMS Laurentic off the coast of Ireland a year prior.

With huge numbers of U-boats sunk by Allied forces since the Germans began their naval offensive in 1917, Hall reasoned that many – particularly those coming outbound from bases in Belgium – would be carrying the latest cipher keys, code books and other intelligence material.

So it came to pass that in April 1918, Damant lead a team of divers to several wrecks in the English channel in search of useful intelligence. Early efforts were often scuppered by older sunken ships, loose rocks or U-boats that held nothing useful.

Their luck changed come 20 May 1918, however, when they found the sunk UB-33 under 84 feet of water.

Getting into the boat was no easy matter: not only was the UB-33 far underwater but it was thought to be located in the middle of an active minefield or, worse still, that the boat was loaded with live mines from its last mission. The divers on Damant’s team were also dressed in late Victorian diving gear, comprising the classic, cumbersome helmet, body weights and lead-soled boots. When one of his men tried to enter the boat through a narrow access hatch, he just could not fit through.

First attempts saw the team use explosives to try and blast their way into hull of the vessel. Though eventually successful, it set off a huge secondary explosion that threatened to injure or kill the other divers.

It cleared the way, though, and once the divers had negotiated the sharp corners and jagged edges of the wreckage (which could snag their air lines to the surface) and ever-present bodies (one diver recalled, “I shall never forget the expression of horror upon some of their faces or the mutilated heads of those who had blown out their brains”) they found a treasure trove: cipher books, experimental weapons and minefield plans were all found aboard and shipped back to London.

Damant’s team moved on to repeat the operation for several other wrecks. Through to the end of the war in November 1918, his team methodically recovered intelligence from at least 15 different wrecks, allowing the Allies to crack German communications even quicker and shift troops to counteract Imperial forces more efficiently.

The best part? Not one diver was seriously injured or killed service, despite the colossal dangers of the operations they undertook.

Years later, Damant and his team were nicknamed the “Tin-Openers” through the Welshman despised the publicity it brought him. It’s only now, 100 years on, that stories about their diving deeds have finally resurfaced.