Around 2,000 years ago, a mixed group of around 400 Germanic tribesmen marched into battle against an unknown opponent. None of them survived.

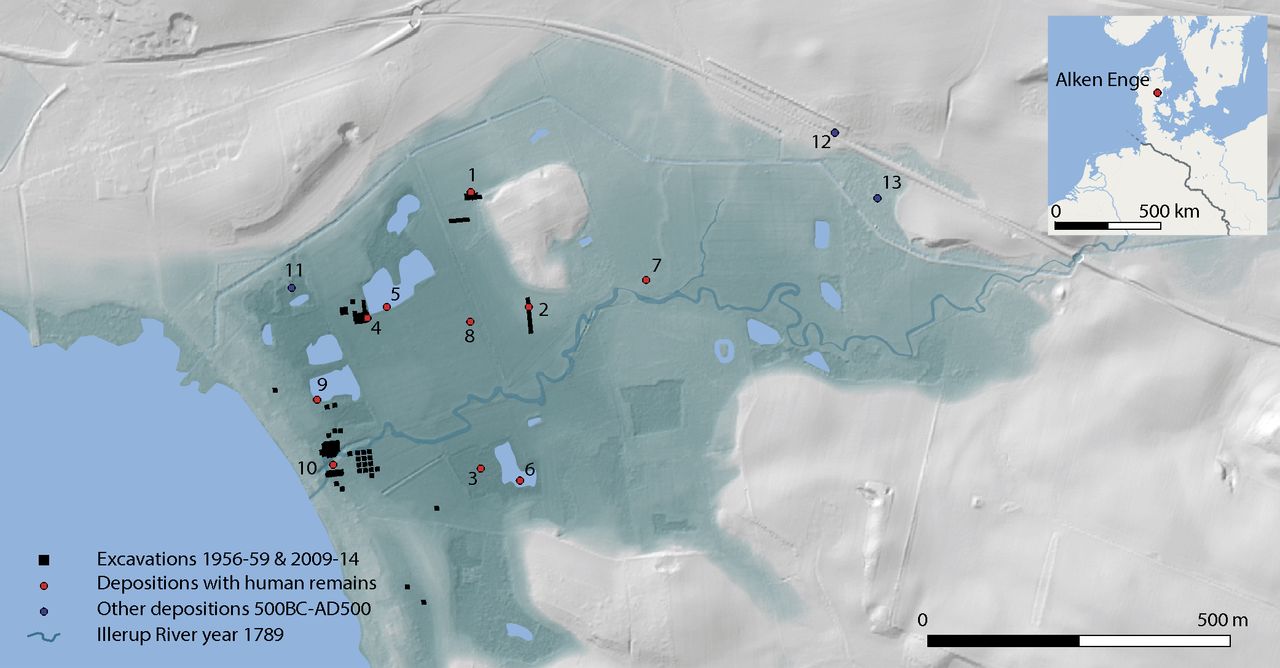

These are the findings of a recent archaelogical dig at Alke Enge – a peat bog nestled among the Illerup River Valley in Denmark – where nearly 2,100 bones belonging to dead tribesman have been recovered.

A new study in a journal called Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences explores how a team of researchers from Aarhus University, also in Denmark, were given further insight into the after-battle rituals common among barbarian tribes in Northern Europe at the height of the Roman Empire’s power.

One of the nearly 400 slaughtered barbarians thought to be buried at Alken Enge in Denmark.

Credit: Holst et al./ PNAS/ CC by 4.0

Though some researchers have hypothesised that the site of the battle may mark a routine foray by the Roman army into the northern-most reaches of the Empire, it is more likely that legionaries did not make it as far as Denmark.

At Alken Enge, the team found more than 2,000 bones and fragments across 185 of wetlands in East Jutland. They suggest that the remains belong to 82 men, most aged between 20 and 40 years old, but probably only account for a “fraction” of the remains likely to be round in the area. After a careful analysis of the surrounding area, the team said that there were likely a minimum of 380 bodies buried on the site in this grizzly fashion.

This population “significantly exceeds the scale of any known Iron Age village community,” the researchers wrote, suggesting the men were recruited from a large area to participate in a common battle.

But who was this battle against? It may have been the Romans themselves: using radiocarbon techniques the bones were dated at between 2 B.C and A.D. 54, coinciding with the reigns of the Roman emperors Augusts and Claudius. This time marked the northernmost expansion of the Empire far into modern-day Germany and Denmark, and at the time some tribes would even have aligned themselves with Rome.

Infighting between neighbours was also, as a result, common. It appears that this might be the simplest explanation for the remains, with ancient non-Roman weapons scattered around the site like axes, clubs and swords.

“The relative absence of healed sharp force trauma suggests that the deposited population did not have considerable previous battle experience,” the researchers wrote. Indeed, the scrappy group of soldiers met “comprehensive slaughter.”

What the team of researchers found particularly interesting was the ritualistic way in which the remains were interred.

For one, they suggest that the bodies of the tribesmen had been left to decompose for up to a year, with nearly 400 of the bones showing some sign of being gnawed or chewed by scavenging animals like foxes, wolves and wild dogs. A conspicuous lack of bacterial decay also implies their inner organs were removed or destroyed before their burial.

Whether it was a friend or foe who did the burying is still unclear. The men’s arm and leg bones were severed from their torsos. Few intact skulls were present and those that were seem to have been smashed with a club or other bludgeoning tool. Four pelvises were hung around a single tree branch with “deliberate intent”, the researhcers wrote.

So, though the Roman Empire and her loyalties may have caused this massacre, the tell-tale signs on the remains paint a picture of two Germanic or Danish peoples meeting in pitched battle.

“The ferocity of the Germanic tribes and peoples and their extremely violent and ritualized behavior in the aftermath of warfare became a trope in the Roman accounts of their barbaric northern neighbors,” the authors concluded.