Second Punic War: The War in Spain

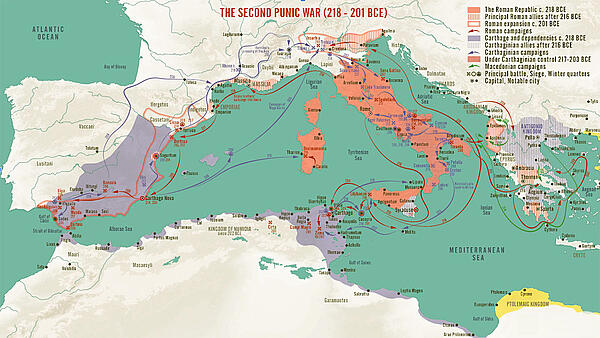

The Second Punic War (218–201 BCE) extended far beyond the Italian peninsula, with critical campaigns in Spain and Africa shaping the conflict’s trajectory. While Hannibal’s invasion of Italy dominates historical memory, Carthage’s ambitions in Spain and Rome’s eventual counterthrust into Africa proved equally decisive. Spain, a Carthaginian stronghold since Hamilcar Barca’s campaigns after the First Punic War, served as both a resource base and a staging ground for Hannibal’s Italian offensive. Meanwhile, Africa, Carthage’s heartland, became the ultimate battleground where Roman resolve would seal the war’s outcome.

The 226 BCE Treaty of the Ebro, intended to demarcate Roman and Carthaginian spheres in Spain, unraveled as Hannibal expanded Barcid control south of the river. Rome’s alliance with Saguntum, a strategic city within Carthage’s claimed territory, ignited hostilities in 219 BCE. After Saguntum’s fall, Roman forces under Gnaeus and Publius Cornelius Scipio launched campaigns to disrupt Carthaginian supply lines and alliances in Spain. These efforts culminated in pivotal clashes such as the Battle of Ilipa (206 BCE), where Scipio Africanus secured Roman dominance on the peninsula.

In Africa, Rome’s daring invasion under Scipio Africanus in 204 BCE shifted the war’s focus to Carthage’s doorstep. Exploiting political fractures among Carthage’s Numidian allies, Scipio’s alliance with Masinissa of Numidia proved critical. The decisive Battle of Zama (202 BCE) ended Carthage’s capacity to resist, underscoring how theaters distant from Italy determined the war’s fate.

Spain

218 BC - Having failed to contain Hannibal in Spain, Rome’s immediate aim was to keep the Carthaginian forces in Spain occupied and thus prevent reinforcements from being sent to Hannibal. In 218, Ganaeus Scipio brought the area north of the Ebro into Roman control. Having defeated Hanno, the Carthaginian commander in the area, Scipio had to deal with Hannibal’s brother Hasdrbal, who had been left in command of Spain. He came north and killed several soldiers but failed to make a few tribes defect to his cause.

217 BC - In 217, Hasdrubal launched naval and land expeditions north of the Ebro, which were defeated by Ganaeus. The latter launched several lightning raids against the Carthaginians. Showing much success, several tribes sent emissaries to Rome. With Hasdrubal occupied by an invading troop of Celtiberians acting on Scipio’s behest, the Senate sent Publius Scipio and reinforcements to his brother to march all the way until Saguntum.

216 BC - The Carthaginian position began to further deteriorate. Hasdrubal, who had retreated to the southwest of Spain, had to deal with a local tribe rebellion and was then ordered to join Hannibal in Italy. Himilco was sent to replace him. Scipios’s task was to keep Hasdrubal in Spain, and when the two armies met, Rome won a convincing victory. This ended any prospect of Hasdrubal joining his brother in Italy in the immediate future and consolidated the Roman position in Spain.

215-212 BC - In 214 and 213, there were revolts by Syphax of Numidia, which led to considerable parts of the Carthaginian army being withdrawn and, thus enabling the Scipios to make further headway in southern Spain. 212 Saguntum was recaptured, and an important town called Castulo rejoined Rome. In seven years, the Scipios prevented Carthage from sending reinforcements to Italy and extended Roman control deep into the territory under Carthaginian control.

211 BC - Rome’s streak of good fortune would finally run out in 211. Faced with three separate Carthaginian armies, the two Scipios decided to split their armies with Publius at Castulo taking on Mago and Hasdrubal, the son of Gisgo, and Gnaeus at Urso to face Hasdrubal, Hannibal’s brother. The Romans relied on the support of a large number of Celtiberian mercenaries who had been persuaded by Hasdrubal to desert. Publius, attempting to cut off reinforcements joining the Carthaginians, was caught by the Carthaginian generals. In the ensuing battle, Scipio was killed, and his army fled. Ganaeus, guessing what had happened to his brother, attempted to retreat but was pursued and brought to the sword. However, much of his army survived. If it had not been for the work of L. Marcius Septimus, a Roman centurion organizing the remains of the Roman army, the Romans might have been driven out of Spain entirely. As it stood, the gains of the last seven years that Rome had managed to make were undone.

210 BC - A new commander had to be found. The assembly chose the son and nephew of the two dead commanders: P. Cornelius Scipio. He arrived in autumn and spent the following years writing his name in history books.

209 BC - Scipio embarked on his first major campaign, the siege of Carthago Nova. Strategically, the city was a tremendously important supply base for Carthage in Spain. Scipio captured the town by sending a wading party across the lagoon that lay north of the city, which, as Scipio discovered, frequently ebbed in the evening. His success meant capturing a considerable amount of booty, both material and human, as well as eighteen ships. Carthage held their political captives in Carthago Nova; upon seizing the city, Scipio released these, which caused many of the local tribes to deflect to him.

208-206 BC- Scipio advanced inland and met Hasdrubal at Baecula, winning the battle. However, Hasdrubal escaped with most of his army into Gaul and went to Italy. Hasdrubal was replaced by Hanno. After several battles which saw Rome victorious, Scipio won decisively at the battle of Ilipa in 206. Hasdrubal fled, and the rest of Roman operations were mopping up operations, removing the Carthaginians from Spain.

Africa

204 BC - Until 204, Roman activity in Africa was confined to lightning raids. There were plans to launch an invasion in 218, but Hannibal’s invasion of Italy quickly stopped those. After a debate with the Senate, Scipio was assigned Sicily with permission to cross Africa if he saw fit. He does so in 204, landing near Utica. A cavalry force under Hanno was defeated, and Scipio began the siege of Utica. In the following spring, a decisive series of events would unfold. Hasdrubal and Syphax had camped near Scipio, who had no alternative but to place his winter quarters on a narrow, rocky peninsula. Their camps, however, were constructed of wood or reeds. The details of the camps were discovered in the course of counterfeited peace negotiations, and a night attack on them resulted in the camps being destroyed by fire and large numbers killed. The Carthaginians recruited fresh forces, and the two armies met at the “Great Plains” about 120 km west of Carthage, where Scipio emerged victorious.

Meanwhile, the Carthaginians had decided to recall Hannibal and Margo from Italy and launch their fleet against Scipio’s ships, which were engaged in the siege of Utica and caught unawares. Scipio, who had camped in sight of Carthage at Tunis, was forced to use a wall of transport ships in defense. Sixty transports were lost, but a major disaster was averted.

Carthage opened peace negotiations, and a provisional agreement was reached. Carthage was to abandon all claims to Italy, Gaul, Spain, and the islands between Italy and Africa. Her rights to expand in Africa were limited. In addition, Carthage was to surrender prisoners and deserters, give up all but twenty ships, and pay a substantial indemnity. The Senate accepted the terms, but during the truce, the Carthaginians, who were suffering from an acute shortage of food, attacked a convoy of Roman supply ships that had been driven ashore near Carthage and followed this with an attack on the boat carrying Roman envoys sent by Scipio to protest about the earlier incident.

Hannibal had now returned to Carthage, and at a meeting with Scipio, he offered peace on the terms of Rome possessing Sicily, Sardinia, Spain, and the islands between Italy and Africa. But Scipio was determined that Carthage should be weakened enough to eliminate the possibility of any further aggressive actions, and so rejected Hannibal’s offer.

The final and decisive conflict, the battle of Zama, saw Scipio victorious again, and the peace settlement concluded after the battle, which contained the following terms: Carthage was to remain free within boundaries as they were before the war. Restitution was to be made of goods seized during the earlier truce. Prisoners and fugitives were to be handed over, and Carthage was to surrender all her elephants and fleet except ten triremes. Carthage was to launch no attack outside her own territory without Roman permission. An indemnity of 10,000 talents was to be paid in fifty annual installments. The assembly ratified the peace and ordered that Scipio was to administer it.

Thus, the Second Punic War came to an end. While nearly shattering Rome, its conclusion left her the most significant power in the Mediterranean and gave birth to Rome as an Empire.

Next: The Third Punic War

MLA Citation/Reference

"Second Punic War: The War in Spain". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.