The First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) marks the inaugural clash between Rome and Carthage, a protracted struggle that transformed Rome from a land-based republic into a naval power capable of challenging Carthage’s maritime dominance.

Chronicled by Polybius and Livy, this conflict, centered on Sicily, unfolded over 23 years, driven by political ambitions and economic stakes.

Unlike the later civil wars, the First Punic War occurred in a Rome still unified by civic purpose, its victory laying the groundwork for the triumphs of Scipio Africanus and the imperial rise under Caesar.

264 BC: The Mamertine Crisis

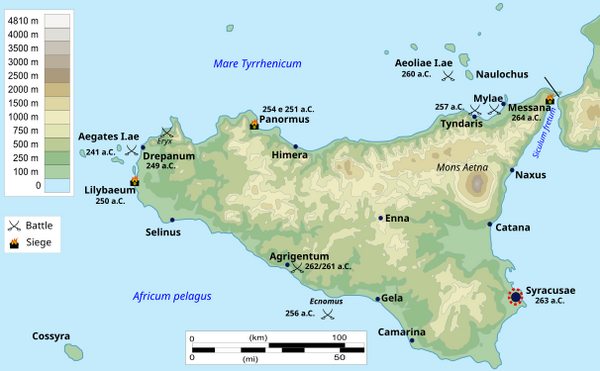

The war’s spark ignited in Messana (modern Messina), where the Mamertines—Campanian mercenaries who seized the city—faced pressure from Hiero II of Syracuse in 264 BC. Appealing to both Carthage and Rome for aid, they exposed Sicily’s strategic value: its grain fields and position astride trade routes. Carthage, a thalassocratic empire with bases in western Sicily (e.g., Lilybaeum), intervened first, garrisoning Messana to protect its maritime interests. Rome’s Senate, initially divided—fearing war with a naval power—yielded to the comitia centuriata’s push for intervention, driven by Consul Appius Claudius Caudex and ambitions for Sicilian resources. Polybius frames the stakes: “Sicily became the prize… Rome chose war over retreat” (Histories, 1.11). Politically, Carthage relied on its Punic oligarchy and mercenary forces, while Rome mobilized its Italian allies, setting the stage for a clash of governance and will.

263–260 BC

Rome’s initial strategy leveraged its terrestrial strength. In 263 BC, Caudex crossed to Sicily, compelling Hiero to defect to Rome after a brief siege of Syracuse, securing eastern Sicily. Carthage, under Hanno, held the west, relying on fortified ports. Rome’s lack of a navy, however, stalled progress—Punic ships dominated the seas, harassing supply lines. Polybius recounts Rome’s pivot: “They built 100 quinqueremes in sixty days, copying a wrecked Punic vessel” (Histories, 1.20). The corvus, a spiked boarding ramp, was introduced, allowing Roman legionaries to grapple enemy ships and fight as infantry.

260 BCE: The Battle of Mylae

The war’s first naval test came at Mylae (modern Milazzo) in 260 BC, where Consul Gaius Duilius faced Hanno’s fleet of 130 ships. Rome’s 100 quinqueremes, crude but equipped with the corvus, met the Punic line off Sicily’s north coast. Hanno’s strategy—ramming and outmaneuvering—faltered as the corvus locked his ships, enabling Roman boarders to overwhelm crews. Livy (via epitome) describes: “The corvus turned the sea into a battlefield… thirty Punic ships sank” (History of Rome, 22.23). Rome captured 14 vessels, losing few, marking its naval debut with a tactical innovation that neutralized Carthage’s seamanship.

259–255 BCE: Land Stalemate and Naval Losses

Rome pressed its advantage, besieging Agrigentum in 259 BC under consuls Lucius Postumius Megellus and Quintus Mamilius Vitulus. A five-month blockade starved the city, forcing Hanno’s retreat, though Hamilcar (not Barca) ambushed Roman stragglers, tempering the victory. Polybius notes: “Agrigentum fell, but Carthage endured” (Histories, 1.19). At sea, Rome’s inexperience cost dearly: in 255 BC, a fleet of 250 ships under Marcus Atilius Regulus wrecked off Cape Pachynus in a storm, losing 100,000 men—Carthage’s weather proving as deadly as its navy. Appian reflects: “The sea reclaimed what Rome had won” (Punic Wars, 1).

255–249 BC: Regulus’s African Campaign

Seeking to end the war, Regulus invaded Africa in 255 BC with 140 ships and 26,000 men, landing near Aspis. His strategy—disrupting Carthage’s heartland—yielded early success: he captured Tunis and 20,000 slaves, pressuring Carthage to negotiate. Overconfident, Regulus demanded harsh terms, prompting Carthage to hire Xanthippus, a Spartan mercenary. At the Bagradas River (254 BC), Xanthippus’s elephants and cavalry encircled Regulus’s 15,000, crushing them with a frontal charge and flank attack. Livy (via epitome) laments: “Regulus fell, his army shattered” (History of Rome, 18.2). Captured and later executed, Regulus’s defeat prolonged the war.

249–241 BC: Naval Resurgence

Carthage regained momentum, repelling Rome at Drepana (249 BC) under Adherbal, whose 100 ships sank 93 Roman vessels in a coastal trap—exploiting Rome’s overextended fleet. Polybius critiques: “Roman haste met Punic cunning” (Histories, 1.51). Undeterred, Rome rebuilt, raising 200 quinqueremes by 242 BC through private loans. Consul Gaius Lutatius Catulus struck at the Aegates Islands (241 BC), intercepting Hanno’s 250-ship relief fleet bound for Sicily. Catulus’s strategy—lightening his ships by offloading ballast—outran Hanno’s laden vessels, ramming and boarding with precision. Appian narrates: “Fifty sank, seventy were taken… Hamilcar’s army starved” (Punic Wars, 2). This victory stranded Carthage’s Sicilian forces, forcing peace.

241 BC: Treaty and Consequences

The Treaty of Lutatius ceded Sicily to Rome—its first province—and imposed a 3,200-talent indemnity over 20 years, payable in silver. Carthage retained Sardinia and Corsica (lost in 238 BC), but its naval supremacy waned. Polybius concludes: “Rome emerged a sea power, Carthage diminished” (Histories, 1.63). Rome’s Senate consolidated control, integrating Sicily into its growing dominion.

Next: The Second Punic War

MLA Citation/Reference

"The First Punic War". HistoryLearning.com. 2026. Web.