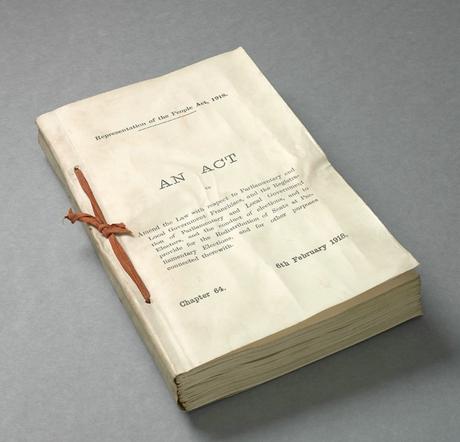

The 1918 Representation of the People Act

The 1918 Representation of the People Act saw significant changes in the electoral system. For the first time, property-owning women over the age of 30 were given the vote. The bill also gave all men over the age of 21 the vote. The Act was partly created in recognition of the sacrifice of so many men for their country - many of whom could not vote before 1918. It also recognised the work of women during the war. The Act was passed by an overwhelming majority in the House of Commons.

The Act is generally seen as a ‘reward’ for the vital work carried out by women during World War One. Before the war, society had generally frowned upon the acts of the Suffragettes, who had drawn attention to their cause through militancy.

However, the war women were integral to the war effort - they worked in munitions factories, as nurses on the frontline, drove buses and even worked in coal mines.

This being said, it is important not to neglect the importance of the pre-war suffragist movement. Through their protests Suffragettes put the subject on the political agenda and after the war, nobody wanted to return to the unrest of prewar Britain.

The dangers of social unrest were illustrated in the Russian Revolution, when the Bolsheviks overthrew the Russian monarchy and government. The British government were keen to avoid such unrest among women as well as men.

The Conservative Party put their support behind their bill because when it became evident that the vast majority of constituencies supported it, meaning their party would benefit from its introduction.

The suffragist movement saw the act as a mark of progress but argued that it should have gone further. It did not answer their demands - suffrage for all, regardless of wealth and gender.

The act on allowed women over the age of 30 to vote, thus barring a large portion of population from the right to vote. The government justified this age limit by claiming that older women were more capable of making educated decisions and less likely to give their support to radical parties.

Ironically, many of the leaders in the pre-1914 suffragist movement were excluded as a large majority were educated women who were in work, living in rented accommodation and unmarried. Those who did not own property and were unmarried were barred from voting.

The Representation of the People Act increased the electorate from 8 to 21 million, yet a huge gulf remained between women and men. It took another 10 years for women over 21 to be given the same voting rights as men in the 1928 Equal Franchise Act, and another 41 years until it was lowered to 18.

See also: Women in World War Two

MLA Citation/Reference

"The 1918 Representation of the People Act". HistoryLearning.com. 2025. Web.