Women's Rights

Throughout the 19th century women were to remain with no political rights, but that is not to say it was not a period for some change for their rights.

In 1839, a new law was introduced stating children aged seven years and under would stay with their mother in the case of a divorce. And then, 18 years later, another law was introduced which all women to divorce husbands if the man was cruel to them.

Other changes included being allowed to keep the money they earned, which came about in 1870, and in 1891, it was decided that women could no longer be forced to live with a husband against their will.

Obviously many of these things would be taken for granted in modern Western society, but these were important change that paved the way for women to gain greater power and independence from men and their husbands.

Queen Victoria proved to a disappointed in her role in the women’s movement though; many hoped she would speak out for women’s rights but she in fact did the opposite, saying in 1870: “Let women be what God intended, a helpmate for man, but with totally different duties and vocations."

Even those who did manage to progress professionally faced constant obstacles. For example, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson qualified as a doctor but failed to get many patients because they would rather see male than a female doctor.

This table outlines the most common areas of employment for women in 1900:

| Type of employment | Number of women employed |

|---|---|

| Domestic servants | 1,740,800 |

| Teachers | 124,000 |

| Nurses | 68,000 |

| Doctors | 212 |

| Architects | 2 |

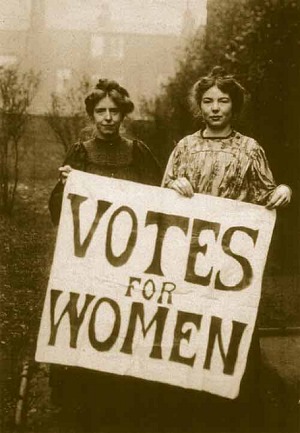

As the 19th century progressed more women pushed for the right to vote. This particular movement is known as the right of suffrage, or simply the right to vote, which is why the women who fought for this right gained the moniker the Suffragettes.

What began as a non-violent movement, which was lead by Millicent Fawcett in the form of National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. She argued that many women earned the same amount of money and paid the same amount as tax as men so should be able to vote.

However, one critic, Frederick Rylands (1896), picked holes in this argument saying if Fawcett had her way: "Political power in many large cities would chiefly be in the hands of young, ill-educated, giddy, and often ill-conducted (badly behaved) girls."

This triggered stronger movement, and in 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst set up the Women's Social and Political Union.

Holding the view that men would not listen to reason, she encourage force to get their point across. They took extreme action, which included attacking politicians, burning churches, and generally disrupting Parliament. Furthermore, when women from this movement were arrested they would often go on hunger strike. The Suffragette movement went on for several decades until women got the vote in 1918 and allowed them to stand for Parliament as MPs in the same year. Finally, by 1928, women gained the same political rights as men.

See also: The Suffragettes

MLA Citation/Reference

"Women's Rights". HistoryLearning.com. 2025. Web.