We are all familiar with the image of Roman sculptures, statues and remains being cast in bland greys or creams, their original colours worn away by centuries of damage or neglect. But one recent discovery by a researcher at the University of Glasgow has perfectly brought to light how even the ancient Romans used bright colours and paints in order to make a point.

Dr Louisa Campbell from the Scottish university’s archaeologist has been using cutting-edge technology to examine remnants of the Antonine Wall, a barrier which used to mark the boundary of the northernmost frontier of the Empire, spanning from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde.

Uusing x-rays, lasers and other techniques, Dr Campbell found that several parts of the Antonine Wall were in fact painted in vibrant yellows and reds in what she calls “Ancient Roman propaganda”, urging the Pictish locals nearby away from Roman territory.

She explained: “These sculptures are propaganda tools used by Rome to demonstrate their power over these and other indigenous groups, it helps the Empire control their frontiers and it has different meanings to different audiences.”

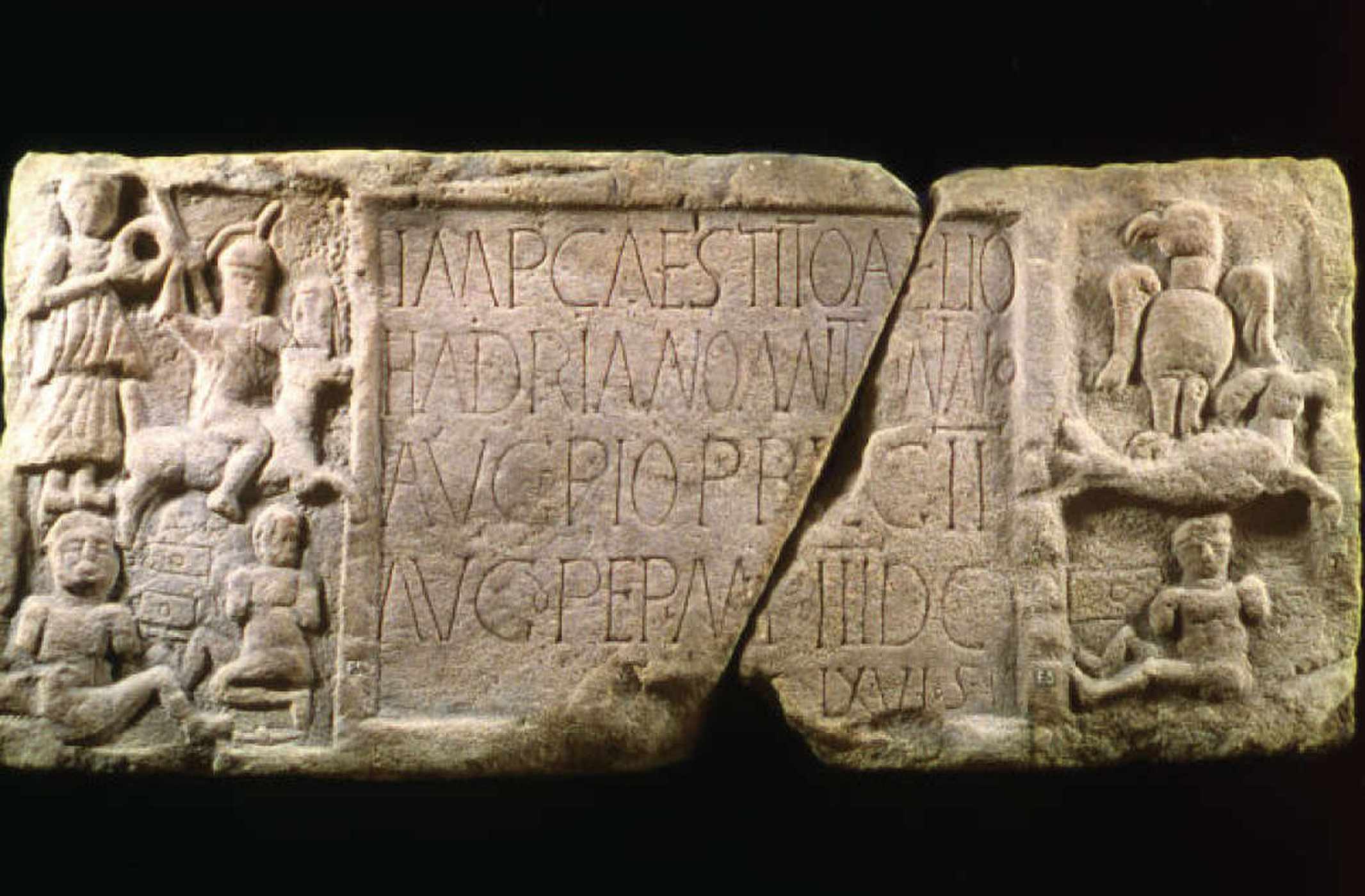

So-called distance stones were unique to the Antonine Wall, which was built in the second century AD, and were used to show how much of it had been built by a particular legion, with each stone belonging to a different detachment and each extolling the Emperor Antoninus Pius. There were 19 in all along the 40 miles of wall, located just 60 miles north of Hadrian’s earlier effort, that Campbell studied.

“They were embedded into prominent positions on the wall (probably crossing points at militarised forts) for full visual impact. The colours would have been a very powerful addition to bring these scenes to life and aid in the subjugation of the northern peoples,” explained Dr Campbell.

A powerful addition they certainly would have been. Dr Campbell’s analysis found that there was a clear method to the applications of different colours: for example, one shade of red was used on letters, Roman cloaks and military standards, various ochres were used in layers to make skin tones, while brighter reds might have been used to depict the spilled blood of Scottish captives. Grim.

In fact, Dr Campbell suggests that one particular red used for the beak of the famous Roman eagle could symbolise the symbolic bird “feasting on the flesh of her enemies”.

The sorts of pigments that the ancient Romans used were likely red and yellow ochre, a red mineral called realgar, a plant dye called madder, a brighter yellow mineral called orpiment and white lead.

Campbell’s research included the two most famous stones from the Antonine Wall: the Summerston slab, which was found on a farm near Glasgow around 1694, and the Bridgeness Slab, discovered in 1868 near the town of Falkirk, at the eastern end of the Antonine Wall.

Both depict particularly bloodthirsty scenes of Roman horsemen charging down Pictish warriors and guarding captive tribesmen who had already been caught and bound. The Bridgeness Slab also shows a beheaded warrior in the middle of battle – both severed ends of the poor Scot’s neck would have been filled in deep, blood-evoking red, says Dr Campbell.

Most of the examples that she studied were discovered between the 17th and 19th centuries and are on display at the University of Glasgow’s Hunterian Museum. Others were found in collections held at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, the Yorkshire Museum in York and the Great North Museum in Newcastle upon Tyne.

“It has been an incredibly exciting opportunity to work with the Hunterian collections and use cutting-edge scientific instruments to undertake non-destructive analysis of important cultural objects,” she noted.